Disclaimer: This article discusses topics at the nexus of investments and taxes, but does not provide and should not be construed as providing tax advice. Please contact your CPA or tax professional for guidance on tax-specific issues.

Note: Please see my video discussion of this topic below or other videos on my videos page. You may also want to read my PDF guide entitled Sensible Strategies to Reduce Your Taxes or other articles regarding retirement accounts on my Research page

This article discusses investment-related taxes. These are the various taxes that surface when you have an investment portfolio held in a taxable account (e.g., not a retirement account). For the purpose of this discussion, please assume the context is always a taxable account unless otherwise specified. I describe three primary examples of investment-related taxes below.

- Capital gains: When you purchase an investment and sell it for more than the purchase price (putting potential depreciation or cost basis changes aside), then you have made a capital gain and this gain may be taxed. The capital gains tax rate is typically lower than the corresponding ordinary income tax rate when it is a long-term (LT) capital gain (i.e., the investment was held for more than one year). Otherwise, it would be a short-term (ST) capital gain and taxed as ordinary income.

- Stock dividends: If you own stocks or stock funds (e.g., mutual funds or ETFs), then you will very likely receive dividends from many of the companies in your portfolio. Most of these dividends will be qualified (for more details on the definition of qualified dividends, please see page 19 of IRS publication 550) and are effectively taxed as capital gains. However, some are classified as non-qualified (a.k.a. ordinary) dividends and are taxed as ordinary income.

- Bond interest: Any interest paid by bonds is taxable as ordinary income. It is worth noting that interest accrued while holding a bond but not paid out (e.g., a zero-coupon bond) is also taxable. Note: Interest from municipal or tax-exempt bonds is generally not taxable.

Some strategies to minimize investment-related taxes

Now that I have defined these primary types of investment-related taxes, let’s discuss ways to minimize them. Below I highlight many of the most common strategies to do so.

I know many investors enjoy picking stocks and investments. However, the math is rather unforgiving as few investors actually beat the market – let alone on an after-tax basis (see Sharpe’s Arithmetic of Active Management but I plan on addressing this in a future blog article/video). Even if one manages to beat the market with their skills, the tax friction can significantly reduce the rate of compounding and their ultimate after-tax return.

Based on the same logic as the previous point, it is sensible to use low-turnover investment mutual funds. Many of these are index funds tracking broad market indices. While many fund products and portfolio managers may advertise tax-aware strategies to address this, there can still trigger significant capital gains taxes.

I believe ETFs represent the greatest invention for the taxable investor in the history of investing. I plan to discuss this is more detail in a future blog article/video but the bottom line is that the IRS has blessed ETFs with a particular tax benefit that allows them to minimize – if not eliminate – taxes from their internal rebalancing (spoiler: they use in-kind creation and redemption). This gives investors and advisors much more control over their taxes. This benefit is so powerful that many mutual fund companies are converting existing funds and launching new ones using the ETF structure. While many people associate ETFs with index investing, even active managers are starting to use the ETF wrapper for their strategies (see this Barron’s article). If you cannot wait for my content, here are two articles discussing this topic from Alpha Architect and the balance.

While similar logic applies to stock dividends, I find high-yield (HY) bonds can be the most problematic from a tax perspective. Recall from above that bond interest is taxed as ordinary income. So HY bonds naturally create more ordinary income. This can significantly increase the taxes on one’s portfolio. One solution could be to place these types of investments in retirement accounts (spoiler: I will discuss this in the context of the broader topic of asset location in my next blog article and video). While unrelated to taxes, I think it is also worth pointing out that HY bonds involve more risk and typically provide less diversification benefit during volatile periods. I rarely use these products for these reasons.

In an effort to support various government entities, the IRS does not directly tax the income from bonds issued by many municipalities. In other words, this makes their interest payments more taxable to investors since they are generally not taxed (though the interest may be used for other tax calculations). However, this is not necessarily a free lunch for investors since the prices of municipal bonds are often pushed up to a point where the resulting yields (intuitively, this can be thought of as the annual interest payments divided by price) are lower than the rest of the market. So one should compare after-tax performance and this depends on their specific tax situation.

When one’s portfolio holds investments that have decreased in value, it can be advantageous to sell those investments to capture the loss (and possibly replace them with similar investments). This loss can allow one to sell other holdings with gains as withdraw funds or rebalance a portfolio with greater tax efficiency. Moreover, the first $3,000 of (net) capital losses can be used to offset income in each calendar year. This makes tax-loss harvesting a potentially valuable strategy. For those in lower tax brackets, tax gain harvesting may also be helpful. That is, investors can make use of their zero tax brackets for capital gains by taking gains that trigger no or little taxes. This can create liquidity for withdrawals or be used to systematically increase the cost basis for some of their holdings. It is worth noting the IRS has put in place various restrictions around these activities (e.g., the wash sale rule). So you should be careful when implementing these strategies.

Under the current tax code (February 2022), inherited assets receive a step-up in basis. That is, even if the deceased previous owner had large gains in an asset, the cost basis is adjusted upward to current market value when they are inherited by someone else. It is worth noting this can include spouses if assets are individually titled (or in a community property state or trust). For example, married couples may find it advantageous to title appreciated assets in the name of the person with the shortest expected longevity.

While I could write an entire book about this topic, the basic idea is that it is very important for retirees to strategically withdraw money from their accounts in such a way to minimize their tax burden over the long term. All too often I see retirees (and accountants!) minimizing taxes in the current year or stubbornly not touching their Roth accounts. This almost inevitable creates a ballooning tax bill somewhere else. Given the way various taxes interact with each other (e.g., see the section below on Income Stacking) this topic is too complex to describe in detail. However, the basic idea is to proactively manage your tax brackets to maximize the after-tax performance of your assets.

While annuity tax benefits are strongly marketed, you have to be very careful; the tax implications can be good or bad depending upon the product and how it is used. One benefit annuities can provide is tax-deferred growth. However, that growth is ultimately taxed as ordinary income. This can be quite punitive for stock-based investments since the growth would only be taxed as capital gain otherwise (i.e., without an annuity). Moreover, the IRS looks at withdrawals on a LIFO (last in first out) basis. That means they assume the first withdrawals will be the growth portion and will thus be taxed as ordinary income. Then the last withdrawals will comprise the original investment basis (return of capital) and not be taxed. This can be good or bad depending upon one’s situation.

While many people are unaware of the distinction, the tax treatment for annuitization is different than for withdrawals. Withdrawals maintain some degree of liquidity to the account from where they are being taken. However, annuitization represents an irreversible decision to convert cash into guaranteed income. As such, the IRS taxes annuitized income differently. While I will not go into the details here, these tax calculations make use of an exclusion ratio to define what portion of each payment is and is not taxable (i.e., interest or growth versus basis). This approach is generally beneficial to investors – especially if they structure their income annuities in an optimal manner (see Optimizing Income Annuity Tax Deferral).

Life insurance is an interesting option in that it represents the only asset (to my knowledge) that can grow on a tax-deferred basis but also incur no tax when paid out (as a death benefit). Of course, Roth accounts tick these boxes but require one to earn money to qualify and then there are contribution limits that constrain the amount one can put into these accounts.

Life insurance policies are increasingly being structured to leverage this benefit from a tax and investment perspective. Moreover, they can do it in such a way (building cash value) whereby the owner can maintain tax-efficient liquidity by borrowing from their policies. Of course, the old saying still stands: Life insurance is not bought; it is sold. So you really have to be careful here too. Less scrupulous agents toss around illustrations and language that can be misleading. One piece of advice if you are considering life insurance: Always ask what the worst-case scenario is. Agents are required to include this guaranteed outcome illustration within broader illustrations. This outcome will not depend on the performance of an index or investment and it will not involve the insurance carrier’s dividend if you are speaking with a mutual insurance company (i.e., a carrier that is owned by its policyholders). In my experience, agents tend to lead with illustrations that are based on some presumed investment performance and are thus not guaranteed.

Another consideration: Income stacking and tax rates

As highlighted above, capital gains and dividends are eligible for tax rates that are typically lower than income tax rates. Moreover, there are multiple tax brackets for capital gains and the standard deduction applies to them as well. However, the calculations of ordinary income and capital gains are not separate; they are combined.

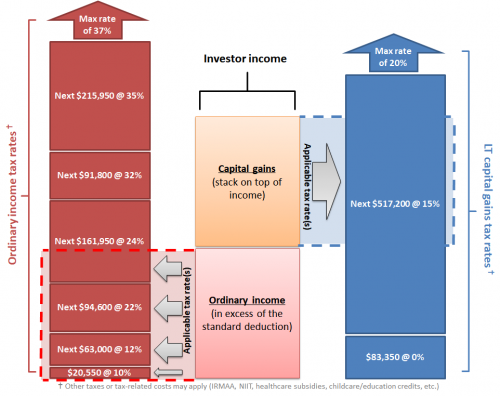

I find the most intuitive way to think about the combined calculation of income and capital gains taxes is to visualize them as being ‘stacked’ with ordinary income on bottom and capital gains on top. However, the ordinary income and capital gains are taxed according to their respective tax brackets and rates.

Ordinary income and LT capital gain stacking

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

Note: I did my best to reflect current tax rates and make this illustration to scale (as of 2022) but both the tax brackets and rates of taxation are subject to change.

Benefits of income ‘stacking’

There are two benefits worth highlighting here. First, stacking income with capital gains on top is beneficial for most tax payers due to the fact income tax rates are significantly higher than LT capital gains tax rates. If the stacking was reversed (with income tax on top of capital gains), then tax bills would generally be higher due to the higher marginal rates on ordinary income For example, last dollar of income depicted in this illustration is taxed at a 15% rate since it is a capital gain. If income were on top, this last dollar of income would be taxed at 35%.

The second benefit derives from the fact that LT capital gains taxation has a 0% tax bracket. This bracket exists above and beyond the standard deduction – which effectively functions like an initial 0% tax bracket itself. This additional 0% tax bracket for capital gains may allow for a significant amount of tax loss harvesting depending on one’s situation.

In retirement, we often want to make use of any spare capacity in lower tax brackets (see my article + video on income tax). However, there is another option: tax-gain harvesting. That’s right: gain harvesting. Some of you might be familiar with tax-loss harvesting but this is different. An example may be instructive.

Example: Let us assume Jane is single, 60 years old, has no ordinary income, and has a portfolio with unrealized capital gains. In this situation, she would be able to realize a significant amount of capital gains without paying any taxes. How is that?

Well, first she has her standard deduction ($12,550 in 2021). So there would be no tax on realized gains up to this amount. Then there is no tax on the capital gains in the first 0% tax bracket (up to $40,400 in 2021). So that means Jane could trigger as much as $52,950 ($12,550 + $40,400) in capital gains without paying a penny in capital gains taxes.

When these situations arise, it is almost always sensible to harvest the gains and re-establish the same or similar positions. This raises the cost basis of these positions and minimizes potential capital gains taxes paid later. However, you must be sure that all of the shares have gains. That is, it is possible that some holdings actually embed a loss even if the average price of that holding embeds a gain. If you sell a position that triggers a loss and then buy it back too quickly, you can violate the wash-sale rule.

Astute readers may have noticed I made two different recommendations for utilizing spare capacity in lower tax brackets: tax-gain harvesting (this article) and Roth conversions (my previous article). Prioritizing between or combining these strategies can be tricky. Complicating matters further are factors such as:

- Tax credits + eligibility for various subsidies (e.g., affordable care)

- IRMMA (investment-related monthly Medicare adjustments)

- NIIT (net investment income tax)

- Taxation of Social Security (watch out for the torpedo!)

As with income tax planning, I strongly advise utilizing a financial planner who uses financial planning software that is devoted to this purpose. I prefer Income Solver due to its superior calculation engine even if its interface and reports are less glamorous than other packages.

Unfortunately, I find many advisors opt for planning software packages that are easier to use and create more aesthetic (interactive) reports to show to their clients. Moreover, I believe it is also important for financial planners to augment software output to address areas the software does not (e.g., disclaiming and beneficiary strategies – see my video discussion of this topic on my videos page).

Related content

- Illustrating the Value of Retirement Accounts

- Quantifying the Value of Retirement Accounts

- Video discussion of this topic on my videos page

- My PDF guide entitled Sensible Strategies to Reduce Your Taxes

You may also learn more about me and my firm here: