RETIREMENT UNIVERSITY

Welcome to my retirement education page! Below I highlight key topics relevant to the topic of retirement planning. This content is not exhaustive but should help you better understand the challenges many face when thinking about or executing a retirement plan. I would love to hear what you think. Please send me feedback!

A few notes

- I tend to focus on the numbers with the content below. However, there is more to retirement than just the financial side. It is a major turning point that will alter virtually all of your priorities – the way you spend your day, how and when you interact with friends and family, and everything else.

- The retirement planning process is often iterative. Information discovered in later steps sometimes requires circling back to earlier steps to refine some numbers or logic.

- If you seek help with your planning or investments, then I recommend watching my videos describing different types of financial professionals.

8 Educational Modules

Financial planning is a core focus for us. It provides a roadmap for managing your finances and portfolios. We find this gives us an demonstrable edge over other firms that focus on solely on your investments or product sales (e.g., life insurance, annuities, or structured notes). While investment management is a critical ingredient and some products may be prudent for your situation, it is important to develop of comprehensive plan first. This way, your financial affairs can be coordinated in an optimal manner.

Firms that focus on product sales often engage in ‘hit and run’ transactions (e.g., variable annuities or whole life insurance) whereby they sell products that pay them quick commissions. Others firms only want to manage your investments, toss them into their firm’s model portfolio, and charge you an ongoing fee. We call these investment-focused types ‘pie chart advisors’ because their financial plans often amount to nothing more than a pie chart summarizing an asset allocation for your portfolio. While asset allocation is another critical element, proper financial planning goes far deeper and considers other factors such as Roth conversions, Social Security, withdrawal strategies, risk management, tax efficiency, etc. Please visit our Retirement University blog for a more information on these and other factors.

In my experience, the goal of saving and investing is ultimately to provide for a secure retirement and any gifting/legacy goals. Whether that need is immediate, impending, or far off in the future, generating retirement income will be a top priority.

Many people tell me they need $X dollars to retire. Some of these figures are based on nothing more than rules of thumb. For example, some people have relied on the 4% rule for withdrawing from a balanced portfolio. That is, it says you should be able to withdraw 4% of your assets in the first year of retirement and then increase that absolute dollar amount by the rate of inflation each year going forward without running out of money.

An Example

If one has one million dollars, then they could take out $40k (4% of $1m) in the first year. If inflation goes up 2% the next year, then they would take out $40.8k ($40k x 1.02) in year two. Then the year three withdrawal would simply increase the previous year’s $40.8k by the new inflation figure. And so forth.

It is worth noting that spending budgets are just estimates and subject to change. There are plenty of studies documenting how spending patterns change through retirement. For example, retirees often spend less on travel and leisure activities, but more on healthcare as they progress through retirement. Accordingly, income planning should incorporate a significant degree of flexibility (i.e., liquidity) for potential changes down the road.

The issue I have with these approaches is that they ignore current market conditions. For example, our current market environment has incredibly low interest rates and dividend yields (as of May 2021). So it is unlikely the same amount of investments will be able to provide for the same amount of income as in previous periods with different market environments.

This is really just another way of saying the valuations of the market change. For stocks, higher price/earnings ratios mean fewer earnings per dollar invested. This usually coincides with lower dividend yields which mean fewer dividends per dollar invested. In the bond market, it just means less interest per dollar invested (i.e., lower yields).

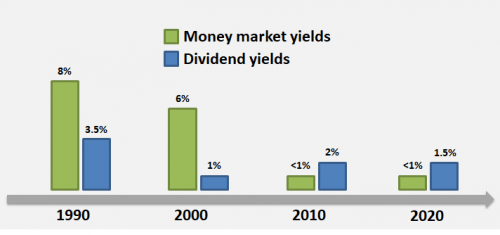

Lower interest rates and dividend yields

Looking at the interest rates and dividend yields over the last few decades makes it clear how things have changed. It may be tempting to complain about the current valuations. However, I think it is worth keeping in mind that the way we have gotten to higher valuations is by rising market prices. In many cases, you’ve likely benefited from the higher capital appreciation which makes these levels of income low.

Conclusion

So for most people nearing or in retirement, I don’t think it is a good idea to equate retirement with a dollar amount of savings. The withdrawal rate is a critical piece of the retirement puzzle and it is not static. Running out of money in retirement is not a situation you want to open the door to.

I think the stakes are just too high to use rules of thumb. I’ve developed a strategy to more precisely estimate withdrawal rates based using current market inputs. So if you are nearing or in retirement, please get in touch to make sure.

Before one retires, it is sensible to first make sure they are ready to do so – both mentally and financially. In terms of finances, one of the first steps is to estimate one’s approximate retirement spending budget and start to consider any legacy-related goals (e.g., money to go to family or charitable causes).

It should go without saying that one should make sure their own personal retirement needs are the top priority; leaving money to heirs and giving money to charities are secondary. As they say on airplanes, put your oxygen mask on first. Only then will you be in a place to help others.

Once we have a better handle on how much income will be needed, we can then compare that figure to the assets (e.g., investments, Social Security, pension, and rental income) to determine whether one has enough to comfortably retire. As discussed in the previous section, one way to do this is to compute a withdrawal rate.

An example

Let us assume one currently requires $75k of income and they have $1 million in investable assets. If they have a pension providing $20k / year and Social Security will provide another $30k / year, then they will only need $25k of income from their portfolio (i.e., $75k – $20k – $30k). That figure works out to be just 2.5% of their portfolio (per year).

Based on my model for retirement income, this 2.5% figure seems reasonable even in the current market environment with low interest rates and dividend yields. However, if this figure came in at, say, 10%, then it would indicate their spending level was too high relative to their assets and could likely jeopardize their retirement security.

Of course, this is a very high-level litmus test. We would also need to consider various other factors such as their age(s) and potential healthcare needs (e.g., we discuss potential assisted living needs in the Risk Management section below).

One of the keys to retirement security is tying down as many loose ends as you can. In particular, we want to minimize the likelihood of liabilities popping up and derailing your retirement plan.

Most people have a good idea about future purchases (e.g., a vacation home) or financial obligations (e.g., kids’ college tuition). However, healthcare needs are not always so easy to estimate. Taking advantage of Medicare and supplemental insurance plans is helpful. However, other potential needs such involving personal care or assisted living can be significant, but difficult to estimate.

Some solutions for long term care

- Insurance: One solution is to purchase long-term care (LTC) insurance. Unfortunately, LTC insurance prices have increased significantly in recent years.

- Family care: Another route is to rely on family support and effectively self-insure. Of course, this requires having family members willing to take on this role.

- Reserves: A third and increasingly popular solution is to create or use existing assets to fund potential LTC needs. For example, many life insurance products now offer accelerated benefit features for precisely this purpose.

Given the potential financial magnitude of this decision and its impact on one’s estate, it is worthy of serious consideration. I encourage clients to discuss various options with their families. In many cases where children are to inherit assets, the decision to insure or not may ultimately impact them more than the insured.

Note: The choices made here may reduce the amount of assets left (e.g., money used to fund a life insurance policy with accelerated benefits) or increase one’s spending through retirement (e.g., to pay for LTC insurance). This may affect retirement feasibility discussed above and/or the investment strategy we discuss next.

Decisions regarding SS can be worth more than $100,000!

Social Security is often the single largest asset one has in retirement. However, more than 90% of people on Social Security (SS) do not maximize their benefits. Unfortunately, the SS system is very complex and SS employees are not allowed to provide advice.

SS benefits differ depending on whether you are single, married, divorced, or widowed. For example, couples face more than 9,000 different options to choose from. This complexity and the need for a more comprehensive perspective make it important to rely on an expert.

Rules of thumb can be dangerous

While rules of thumb can help with intuition, they can also be dangerous. SS elections impact other parts of your financial picture. So these decisions should not be made in a vacuum. Instead, they should be coordinated with your strategies for other investments and assets.

Given this complexity, I believe Social Security and broader retirement decisions should leverage insights from proper financial planning tools. I regularly see cases where rules of thumb and conventional wisdom unnecessarily miss out on $100,000, $200,000, or more in benefits and tax reductions.

For those interested in learning more about Social Security, I recommend reading Mike Piper’s book on Social Security and using his free online Social Security tool. If you really want to roll up your sleeves, then I also recommend Bill Reichenstein’s research and software firm.

At the risk of pointing out the obvious, it is imperative to use a conservative approach to investing during retirement. Indeed, nobody wants to run out of money or be forced to reduce their standard of living during retirement.

One aspect of a conservative approach is to use the right tools – investment vehicles that have low or reasonable costs and are tax-efficient. Below I offer three suggestions to help guide these decisions.

- Use low-cost exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and direct investment

- Avoid costly and tax-inefficient mutual funds with high turnover

- Avoid variable annuities (except possibly for advanced estate planning – see last module)

Note: If a financial professional makes any recommendations that conflict with these ideas, then they and/or their firm are likely receiving commissions or other kickbacks for selling specific investment products.

Calculating what you need from your liquid assets

Once we have reasonable estimates for a retirement budget (which, again, is not written in stone), we must determine how your assets will provide for that spending. Of course, some have other guaranteed sources of income that will cover part of this budget (a pension, Social Security, etc.). So we subtract these sources of income from your total spending budget to determine how much income we need specifically from your liquid investments.

Now we need to build a portfolio that provides the income we need while allowing enough flexibility to accommodate for changes (or surprises) down the road.

Start simple: A balanced portfolio

In general, I recommend investment strategies that start with a balanced portfolio. If we assume a simple portfolio with just stocks and fixed income (e.g., bonds + cash) allocations, then the goal will be to balance multiple factors including:

- Need for growth: Some people need growth in order to meet their needs. This factor can help determine the minimum allocation to growth investments (e.g., stocks).

- Capacity for risk: Some financial situations can only afford to take a certain amount of risk. This factor can help determine the maximum allocation to growth investments.

- Tolerance for risk: Each investor can only stomach so much risk. Very few people can sleep at night if their portfolio were to fall 20, 30, or 40%. This factor also helps determine the maximum allocation to growth investments.

As I highlighted in the module on retirement feasibility, there are rules of thumb that are used to calibrate portfolios based on varying levels of withdrawals. However, many of these rely on history repeating itself to some degree or some complicated math and statistics.

I have developed my own approach to determining retirement feasibility and calibrating portfolios. It is much more transparent and intuitive. So I find it makes clients more comfortable.

Other details

This section has brushed some details under the rug here. As highlighted above, decisions around Social Security are a key factor. Maximizing these benefits is a multi-dimensional challenge. One may be tempted to look at their own life expectancy for deciding to file or delay. I like to compare this to market-based options since Social Security income can be viewed as an inflation-adjusted annuity.

If a spouse or partner is involved, then this requires a little more thought to maximize the total benefits including spousal options. Moreover, Social Security decisions can also impact taxes. I touch on this angle in the next module on tax efficiency. The bottom line is that Social Security decisions should account for the broader planning context and not be made in a vacuum.

For more information on my preferred strategy for investment income, you can visit this page or watch this video.

Disclaimer: I discuss topics at the nexus of investments and taxes. While I regular liaise and work with them, I am not an accountant, certified public accountant (CPA), or tax professional. Accordingly, this content is not and should not be construed as tax advice. Investors should seek advice from a CPA or qualified tax professional for any questions or issues related to taxes.

I break taxes down into two different, but related dimensions. The first is what most people focus on: income tax. The second dimension focuses on those investment-related taxes triggered by dividends, interest, and capital gains.

Income tax

When it comes to income tax in retirement (and before), one broad approach is to attempt to level out the realization of income. You might ask, what does that mean? First, one must understand that we have a progressive tax system in the United States. That is, tax rates generally increase as income rises (on marginal dollars of income).

Consider a situation where one has the choice between earning $100k in a single year or $50k in each of two years. The latter scenario typically results in a lower tax bill since a higher marginal tax rate would apply to the second $50k when stacked on top of the original $50k in a single year.

This notion can be generalized. For example, one can level out the realization of income throughout their retirement as to minimize poking their head up into higher brackets. Unfortunately, it is not always this simple.

Income-related factors

Whether they are called taxes, subsidy reductions, or something else, we should also be mindful of minimizing the impact of other costs that are triggered by levels of income. Here are three examples:

- IRMAA: This is short for investment-related monthly adjustment amount. In a nutshell, you will end up paying more for your Part B or Part D premiums if your adjusted gross income (AGI) is above a certain level.

- NIIT: This is short for net investment income tax. In a nutshell, this is effectively an additional tax on passive investment income that applies if your modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) is above a certain level.

- Social Security: The amount of Social Security that counts as income (and is thus taxed) can be zero, 50%, or 85% depending upon your overall income. As a result, additional income in a given period can make more of your (SS) income taxable.

It is worth noting that these additional costs can be triggered by just one extra dollar of income. The spike-like nature of these costs can make them more punitive than the tax credits and other benefits that phase out gradually with higher levels of income (e.g., educational, childcare, and earned income credits).

Big picture

Suffice to say, it is important to take a step back and look at the bigger picture when thinking about income-related taxes and costs. Below I highlight a few of the primary tools we can use to optimize our individual tax situations:

- We can decide whether to take money from taxable accounts, traditional retirement accounts (e.g., 401Ks and IRAs), or tax-free retirement accounts (e.g., Roth IRAs). A withdrawal from a traditional IRA will trigger income, but not when taken from a Roth IRA.

- We can also use spare capacity within a given tax bracket to move IRA money to the tax free side via Roth IRA conversions.

- Delaying Social Security and required minimum distributions (RMDs) can often be an advantageous strategy during retirement. The idea is to create a period of very low income and use it to convert IRAs to Roth IRAs at lower tax rates.

- Consider strategically assigning beneficiaries to your traditional and Roth IRAs. Even without full stretch benefits of previous years, directing traditional (Roth) IRAs to lower (higher) income children or beneficiaries can reduce the overall amount of income tax ultimately paid.

- Charitable giving can also reduces taxes if done properly (but you are giving away money!). We discuss this in the next module.

- I find income annuities to be an underutilized tool for tax optimization. The flexibility they provide in structuring income and their beneficial tax treatment (i.e., exclusion ratio) can make them very useful.

While many people want one or more rules of thumb, the unfortunate truth is that the tax code is complex and everyone’s situation is unique. Even with access to the most sophisticated planning software, I find I must conduct my own external analysis and optimizations in order to truly maximize results for my clients.

Investment-related taxes

The income-related taxation I just described is usually the 800lb gorilla, but that does not mean we should ignore other areas to minimize our taxes. Indeed, I find investment-related taxes offer more low-hanging fruit.

As highlighted above, I mostly use low-cost, tax-efficient exchange-traded funds (ETFs). Many people attribute their tax efficiency to low turnover (and hence fewer capital gains), but the benefit is stronger than that. Indeed, I often say ETFs are the best invention in the history of investing for the taxable investor.

The ETF advantage

Why do I say this? I will not delve into the details here, but ETFs have a special blessing from the IRS that effectively allows them to rebalance their portfolios without triggering capital gains for their investors (the curious can read this article). In contrast, mutual funds often distribute significant capital gains to their investors when they buy and sell within their portfolios.

Of course, if you sell an ETF you purchased at a higher price than you bought it, then you will pay taxes. However, its returns can compound at a higher rate when there is less tax friction along the way. Moreover, if one holds onto an ETF until they pass, then their heirs will likely receive a step-up in basis (according to the tax law as of this writing – May 2021).

This step-up feature is why tax-efficient equity investments should often be held in taxable accounts or tax-free accounts (e.g., Roth). If all of that growth took place within a traditional IRA, then the growth would eventually be taxed as ordinary income when it was distributed. This notion is part of what is called an asset location strategy (placement of assets in accounts with different taxation) – not to be confused with asset allocation (i.e., the division of assets into different asset classes).

There are more strategies (e..g, municipal bonds), but this section is already quite long. However, I do discuss a few more advanced planning strategies in the last module.

I am always happy to help facilitate philanthropic activities. Many times, my clients already have charitable causes in mind. Other times, I am asked to conduct due diligence.

For example, I have come across charitable causes that were more charitable to the executives and staff employed by the entity than to the actual cause. Whether this occurred by design or chance, the actual cause received less money or benefits than the employees. Intentions are one thing, but execution is another.

It is also worth monitoring the financials of different charities. Significant financial mismanagement can make causes less efficient and reduce their long-term viability.

Tax-efficient giving

Tax efficiency is another angle to consider. For those already inclined to give, there can be significant tax benefits if gifting is properly structured. Donating money that has yet to be taxed is one way to increase tax efficiency.

For example, one might consider qualified charitable donations (QCDs) directly from their IRAs (there are, of course, restrictions and eligibility requirements). These donations would go directly to the chosen charities in full without requiring tax being paid as with normal IRA distributions. Moreover, they would lower RMDs in future years since the IRA balance would be reduced.

Alternatively, one could use a donor-advised fund (DAF). In this scenario, they would contribute to the DAF and receive the tax benefits in that year. However, they would not have to choose the specific charities right away. They could make grants to charities of their choice (again, some restrictions and eligibility requirements apply) from that fund down the road as they please.

In addition to the details highlighted above, there are various legal and administrative logistics worth mentioning. On the legal side, there are several estate planning tasks I believe everyone should get sorted.

- Last will and testament: Allows you to specify what happens to your estate (i.e., property in your name) after your death.

- Living will: Also known as a directive or advance directive (to physicians), this document allows people to indicate their wishes for end-of-life medical care in the event they cannot communicate their decisions themselves.

- Powers of attorney (POA): These documents can give others the authority to make decisions regarding your healthcare, finances, etc. Note: While successor trustees can access and control assets within a trust, a POA with specific language is required for others to access and manage retirement accounts (e.g., an IRA or 401K).

- Trusts, legal titling, and beneficiary designations: These tools can help make things go where you want after death while avoiding probate. The last thing many people want is for their estate to get caught up in the courts (i.e., probate). It is important to understand these maneuvers supersede directions in a will. Note: Trusts are not just for the very wealthy.

- Guardianship: If applicable, one should designate who should receive legal guardianship of children in the event of one’s incapacity or death.

- Letter of instruction: Technically, this is not a legal or binding document. However, a letter of instruction can help your affairs get sorted more efficiently after you pass. It would typically list relevant financial information (assets, records, agreements, etc.) and could be very useful to your family or an executor. Note: A secure, fireproof document storage box comes to mind.

Simplify

I also advise clients to simplify and automate their financial affairs to the extent they are comfortable. For example, many retirees are unaware of bill pay services offered by banks. Ditto that for automatically transferring investment income from their brokerage accounts into the bank accounts. Filling out one simple form to direct any dividends or interest to one’s bank account can save much time and effort.

In some cases, I can put virtually all of one’s recurring finances on autopilot. Of course, this should be regularly monitored to make sure all is in order. However, I find this kind of automation provides significant relief to many as their desire or capacity to keep all of their financial fairs in order can diminish through time.

This section focuses on advanced planning needs. In particular, I highlight a few of the issues and solutions faced by the ultra-wealthy.

Estate taxes

One of the biggest issues faced by the very wealthy is how to transfer their assets to their children, grandchildren, etc. In particular, the US government has historically imposed a tax on generational wealth transfers that exceed certain levels.

Right now, that estate tax exemption is over $11.7 million per person (effectively double that for married couples). That is, the estate tax does not apply to the first $11.7 million transferred. Moreover, the highest tax that would apply is 40%.

For very large estates, there are multiple options that may help reduce, if not eliminate, the estate tax bill. I highlight some of them here:

- Pre-growth transfers: Many people shift ownership of assets with high growth potential out of their estate before they appreciate. For example, a family who plans to take their business public may want to transfer some of the ownership equity before an IPO.

- Discounts: Everyone knows committee decisions can be contentious and inefficient. Accordingly, attorneys can place assets into an entity (e.g., family limited partnership) where multiple family members have minority or non-controlling interests. This multi-tiered ownership structure and lack of marketability can receive a valuation discount. So this can decrease the value of those assets within one’s estate.

- Asset freezes: The IRS sets a level of return (called the required rate). Let us assume one (i.e., the grantor) set up a trust and funded it with $100. Moreover, they set up the trust to receive future cash flows and leave everything else to a beneficiary. At inception, one would calculate the value of the promised future cash flows using the required rate. In many cases, one constructs these cash flows in such a way so their current value is $100. This makes the gift to the beneficiary precisely zero. Let us further assume the assets in the trust grow in excess of the required rate. In this case, the excess growth will effectively spill out of the estate. That is, it will go to the beneficiary without using the estate tax exemption or gifting capacity. In effect, this freezes one portion of the grantor’s estate. It only grows by the required rate which is typically reflective of the rate of inflation.

- Annual gifting: While this often amounts to rounding error for large estates faced with estate tax issues, one is allowed to make an unlimited number of $15k (currently) gifts to other people. For married couples, this effectively doubles the limit. For example, consider a couple with three children. They can gift up to $90k without using their estate tax exemption or gifting capacity. That is, both parents can give $15k to each child ($15k x 3 children x 2 spouses).

- Market stress: Transferring assets out of an estate after significant market declines can provide a better bang for the buck – assuming the investments will likely recover over the long term.

- Roth conversions: Paying taxes to convert traditional IRAs into Roth IRAs may be a sensible means of reducing the size of your estate – even if the income taxes are higher than those that would be paid by the beneficiaries.

- Charity: Give money away to charities or set up a foundation that would make grants to charities down the road. This can certainly address the estate tax issue, but it involves kissing money or assets goodbye to a large extent. At the same time, it is common to use a family foundation to employ children or other family members.

- Life insurance: One purpose of life insurance is to help fund estate tax bills. If structured properly, life insurance can grow tax-free. Moreover, the proceeds can help mitigate the need for liquidating assets to pay an estate tax bill. This can be a particularly useful strategy when many of the assets are not liquid. Examples include operating businesses, farms, and real estate.

In addition to the financial, tax, and control factors, philosophical reasoning can drive estate tax decisions as well. When giving money to children, grandchildren, or others, how much is enough?

“I still believe in the philosophy … that a very rich person should leave his kids enough to do anything but not enough to do nothing.“- Warren Buffett

Investment-related taxes

For large estates, investment income can often rival, if not dwarf, other taxable cash flows. That is, dividends and interest may exceed a family’s income from operating businesses or employment activities. Moreover, much of this money typically resides in trust. So its tax treatment often reaches the highest federal marginal income tax rate at much lower thresholds than individual taxpayers.

All of these factors can make investment-related taxes a major concern. Private placement life insurance (PPLI) and private placement variable annuity (PPVA) products can be helpful in this context.

The overriding goal here is to leverage the tax shielding benefits of these products. Of course, these products would both impose various costs to implement. However, the tax benefits can often outweigh these costs – especially when state taxes are also relevant.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

|

|

More information

If you are thinking about retirement, you might find these links helpful: