Disclaimer: This article explains some potential options related to investing but does not constitute investment advice. Please get in touch if you would like to discuss your particular situation.

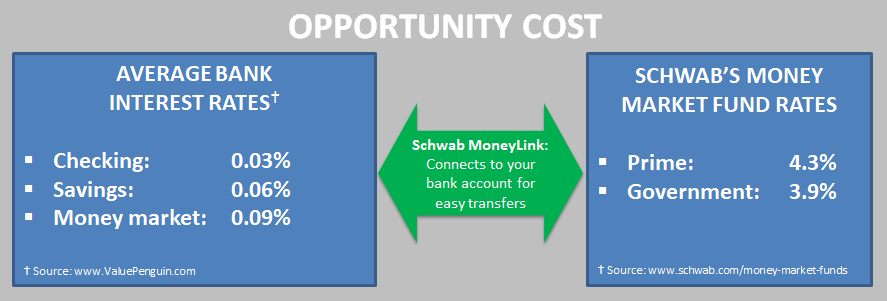

After years of near-zero interest rates, it is no surprise many people have left cash sitting around their checking, savings, and brokerage accounts. When rates were lower, there was little opportunity cost. However, that is no longer the case. Indeed, one glass-half-full takeaway from the investment malaise of 2022 would be the higher rates that are now available. Specifically, we now have much better opportunities to invest our cash than a year ago.

While banks have increased their rates in checking and money market accounts (MMAs), they still appear to be lower than many of the money market funds that can be easily accessed via brokerage platforms like Charles Schwab. For those who are not familiar with these investment options, money markets are generally viewed as a safe place with low risk where you can earn competitive rates of interest on your money. You can click here for Investopedia’s description of money market accounts and funds.

Given our newly found opportunity cost of leaving cash idle, I have found myself repeatedly explaining low-risk options for investing idle cash. So I thought it would be sensible to write a quick article summarizing the process. Hence this article!

For the most part, the following discussion explains how to invest using the Charles Schwab platform but I am sure you can do this with most major brokerage firms. I have broken the process down into three convenient steps:

1. Open an account

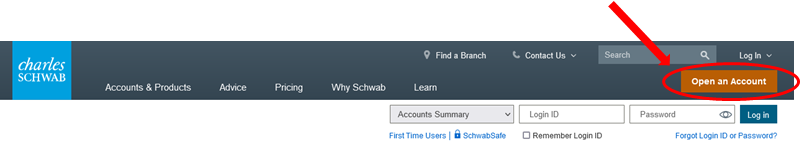

The first step is to open an account. If you do not already have an account at Charles Schwab, you can easily do this by clicking on the brown-ish OPEN AN ACCOUNT button located in the top right corner of www.Schwab.com.

The directions are relatively easy to follow but Schwab has excellent customer service (1-800-435-4000) should you need some assistance.

2. Transfer money & Schwab MoneyLink

Once your account is set up, you will need to move money into it. There are a variety of ways to do this (e.g., wire the money or send a check) but I find Schwab’s MoneyLink tool offers the most convenience. This tool allows you to easily transfer money between your bank and Schwab accounts. However, you do have to set up Moneylink first.

You can do this manually by filling out and submitting the Schwab MoneyLink form (accessible here: https://www.schwab.com/resource/moneylink-electronic-funds-transfer-form). However, I find it is easiest to set up MoneyLink from within your Schwab account. Of course, I can do most of this for you but you would have to be a client!

Note: The Moneylink setup process will typically only take 10-15 minutes in total time spent but will be spread over a couple of days for the deposit/withdrawal step detailed below.

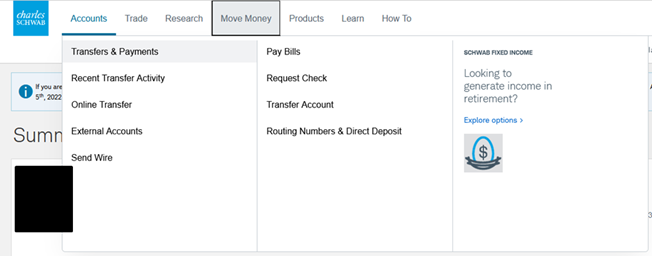

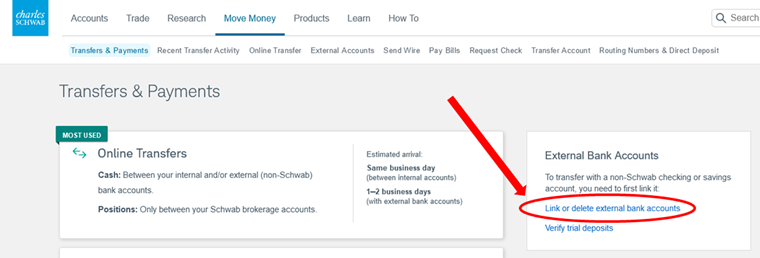

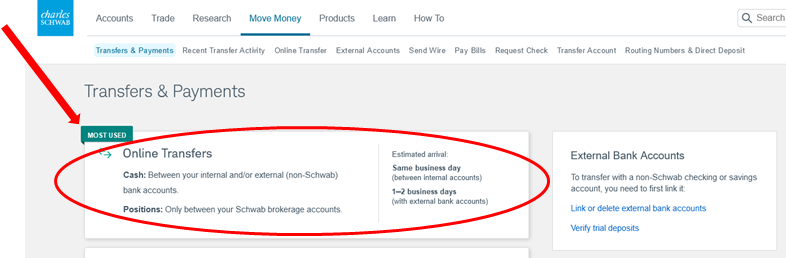

Once you are logged in, simply choose the MOVE MONEY tab at the top and the corresponding TRANSFER & PAYMENTS option (see the screenshot above). Then you will see a link for connecting your bank account (see the screenshot below).

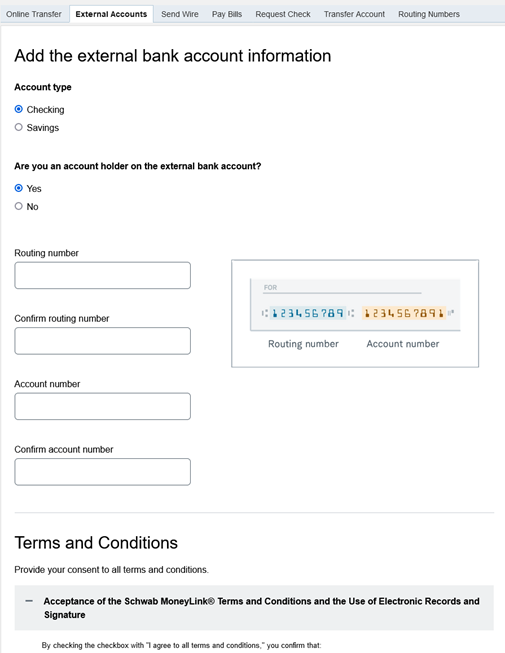

This link will take you to another screen where you enter the details for your bank account. You will just need your banks routing number and your account number. If you do not know these, you can get them from the bottom of a check for that account (for checking accounts, of course). The screenshot below shows the inputs. As you can see, you should be listed as an account holder on the bank account as well.

Once you have completed this step, Schwab will make a couple of small deposits and withdrawals into and from your bank account (e.g., $0.06 and $0.13). Then they will ask you to confirm these figures to ensure that it is indeed the right bank account.

Et voile! Once you have completed this process, you should not have access to transfer money between Schwab and your bank account. Moving money is super simple and can be done via Schwab’s app (phone or tablet) or a web browser.

You just go to the same TRANSFER & PAYMENTS screen (under the MOVE MONEY tab) and choose the ONLINE TRANSFER option at the top of the page. From there, the directions should relatively straightforward. You will select the source account (your bank account where the money is coming from) and then select the destination account at Schwab (where the money is going to). NOTE: Transfer money to your brokerage or living trust account – NOT your retirement accounts as that would constitute a retirement contribution. Lastly, you will specify how much money to transfer. Then it usually only takes one business day (maybe two if you do this later in the afternoon) for the money to transfer.

3. Invest the funds

The last step is to invest the funds that are now in your Schwab account. I cannot give general investment advice here but I will mention several options. Moreover, I will not go into much detail about these investment options as that would bloat the size of this article which is already longer than I anticipated.

Note: Unless otherwise mentions, all of the following investments can be implemented via the TRADE tab when you are logged into your Schwab account.

Money market funds

One of the easiest options is to invest in money market funds. Here is a link to various money market funds Schwab offers. You will see various types of money market funds. Just pick the one that is most appropriate for your situation, invest your money, and then take it out when you need it.

There are three primary categories – some of which are split into subcategories and tiers based on the size of your investment:

- Prime money market funds: Invest in a diversified portfolio of short-term, high quality corporate and government bonds.

- Government market funds: Invest in a diversified portfolio of short-term government bonds.

- Municipal money market funds: Invest in a diversified portfolio of short-term municipal bonds.

CDs and bonds

You could also purchase certificates of deposit, treasury, or other low-risk bonds. Schwab’s fixed income tab displays many of these options so that it is easy to compare their interest rates across a variety of maturities. While holding any of these investments to maturity should result in getting your original investment back with interest, changes in interest rates could impact the value of these investments in the interim.

Multi-year guaranteed annuities (MYGAs)

One more option many investors favor is the multi-year guaranteed annuity or MYGA. This product is very similar to a CD but is only offered through insurance companies. Like a CD, a MYGA offers a fixed and guaranteed rate of interest based on the maturity chosen (e.g., 2-year versus 3-year).

Note: MYGAs are not accessible on the Schwab platform but I would be happy to assist you. I am an independent agent who can help you find the best rate by obtaining quotes from a variety of high-quality insurance carriers. Please get in touch if you are considering a MYGA or other type of annuity.

Another similarity is that an MYGA will also impose a penalty for money withdrawn before the contractually guaranteed period. However, one advantage MYGAs also have is a provision whereby investors can take out a certain amount of money each year without penalty before the product maturity. While investors may appreciate this extra penalty-free liquidity, there are two other factors that I believe investors find most attractive about MYGAs.

The first is its interest rate. MYGAs often offer rates that are higher than comparable CDs or bonds. However, you should exercise some caution. Just like bonds, lower-quality issuers typically offer higher interest rates to compensate for the higher risk. So I recommend only buying annuities (or bonds) from higher quality insurance companies with A-ratings. This article provides a nice summary and comparison of CDs, bonds, and MYGAs.

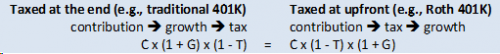

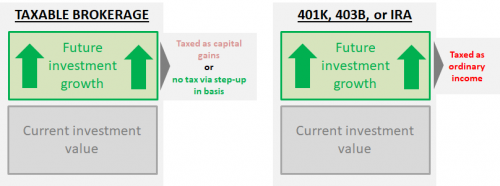

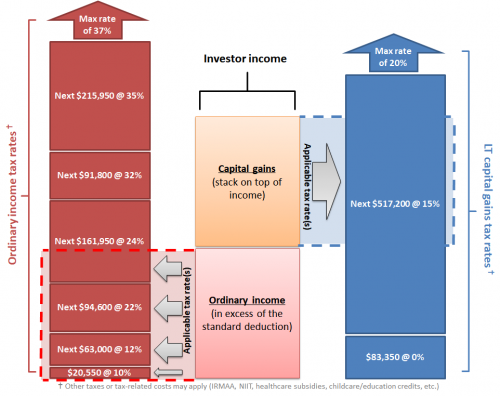

The second factor that I believe attracts the most investors to MYGAs is their tax deferral. While interest is taxed along the way for CDs and bonds, MYGAs (like many annuity products) are only taxed when money is taken out. So they can allow your investment to compound without tax friction. Moreover, this gives investors more control over their taxation.

For example, one common application arises when someone is just a few years away from retirement. Instead of investing in a bond or CD and triggering taxes while they are still employed, a MYGA could allow them to defer the taxation of this investment until they are in retirement and presumably in a lower tax bracket.

Summary

This article outlined some simple steps that can allow you to start generating more interest on your idle money. It also highlighted the various types of low-risk investments that are available. I hope it was helpful but please do not hesitate to reach out if you have any questions.