I spent some time on Google, but could not ascertain the origins of the term fixed income. Presumably, it was just a simple description given to investments where all of the related cash flows were dictated per contractual obligation. For example, this could be something as simple as a government bond that pays fixed coupons and returns the principal at maturity. However, the term fixed income has now come to describe pretty much any investment obligated to pay a pre-specified stream of cash flows – some of which are more complex (e.g., mortgage-backed securities).

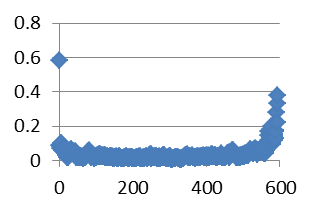

Brushing some details under the rug (e.g., some bonds can be called), fixed income investments effectively allow investors to purchase future cash flows with a high degree of certainty. However, it is important to note this degree of certainty only applies when the investments are held to maturity.

If an investment is sold before it matures, the sales proceeds will naturally be at the mercy of the market. Other investors will take into account the remainder of the cash flows to be paid and discount them via relevant interest rates. Thus, in the case where fixed income investments are not held to maturity, much of the certainty can be lost.

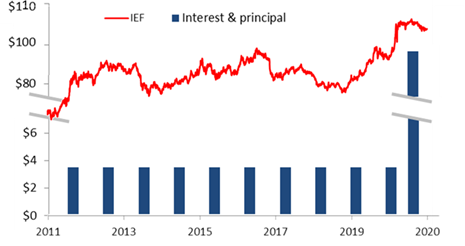

Without doubt, the high turnover of many bond funds can naturally destroy this essence of fixed income. Moreover, advocates of total return investing also seem to disregard the inherent stability of contractual cash flows as they put portfolio income right back into the market even when the ultimate goal is income.

This article attempts to restore this sanctity of fixed income. In particular, I advocate for the design and utilization of fixed cash flows in the context of asset-liability management (ALM) – thereby mitigating, if not avoiding, market volatility. While relevant to other investment mandates (e.g., private foundations with cash flow liabilities), I discuss this notion in the context of retirement income.

I use bond ladders and income annuities to highlight some potential benefits of this approach. In addition to potential cost and tax savings, the math behind this approach (i.e., time value of money) is much simpler than many of the statistical models used for portfolio management. Accordingly, I believe this approach can facilitate greater understanding and peace of mind for many investors. Retirement income is one natural application for this strategy. However, it can also be helpful in estate planning for blended families and other situations where one wishes to manage multiple beneficiaries’ claims to income and principal.

Note: Readers interested in this topic may also like to read an earlier article I wrote (Destroying Stable Income Streams) that focuses on a similar topic, but primarily in the context of dividends.

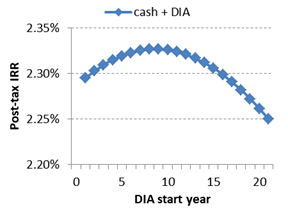

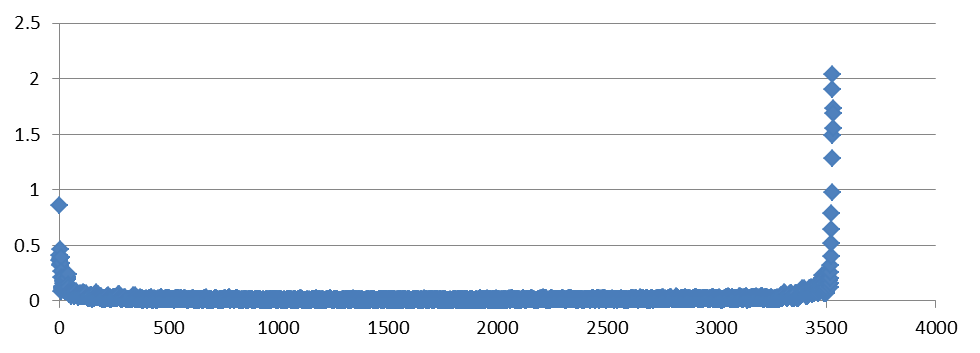

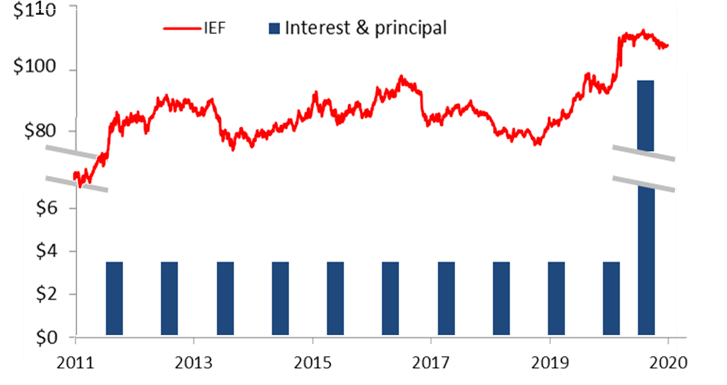

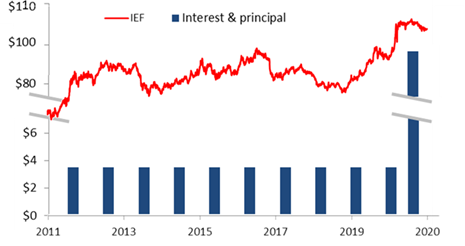

| Figure 1: 10-year bond cash flows vs IEF price

Source: Aaron Brask Capital |

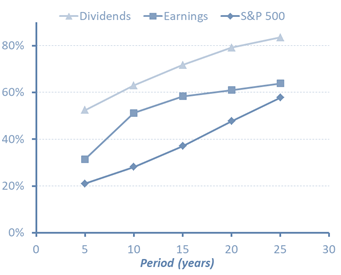

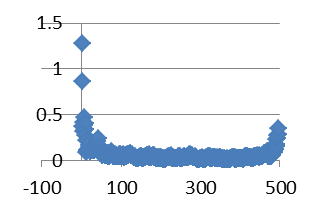

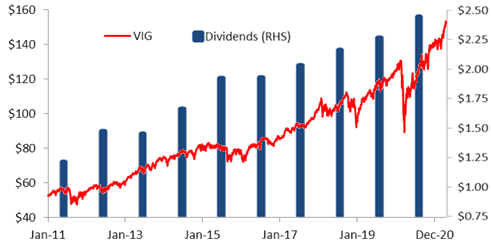

Figure 2: Dividend cash flows vs market price (VIG)

Source: Aaron Brask Capital Source: Aaron Brask Capital

|

Background

| Note: This article focuses on the context of retirement income, but it is worth noting the ideas are also relevant to other investment applications where one is tasked with addressing liabilities in the form of future outgoing cash flows (e.g., pensions, endowments, private foundations, etc.). |

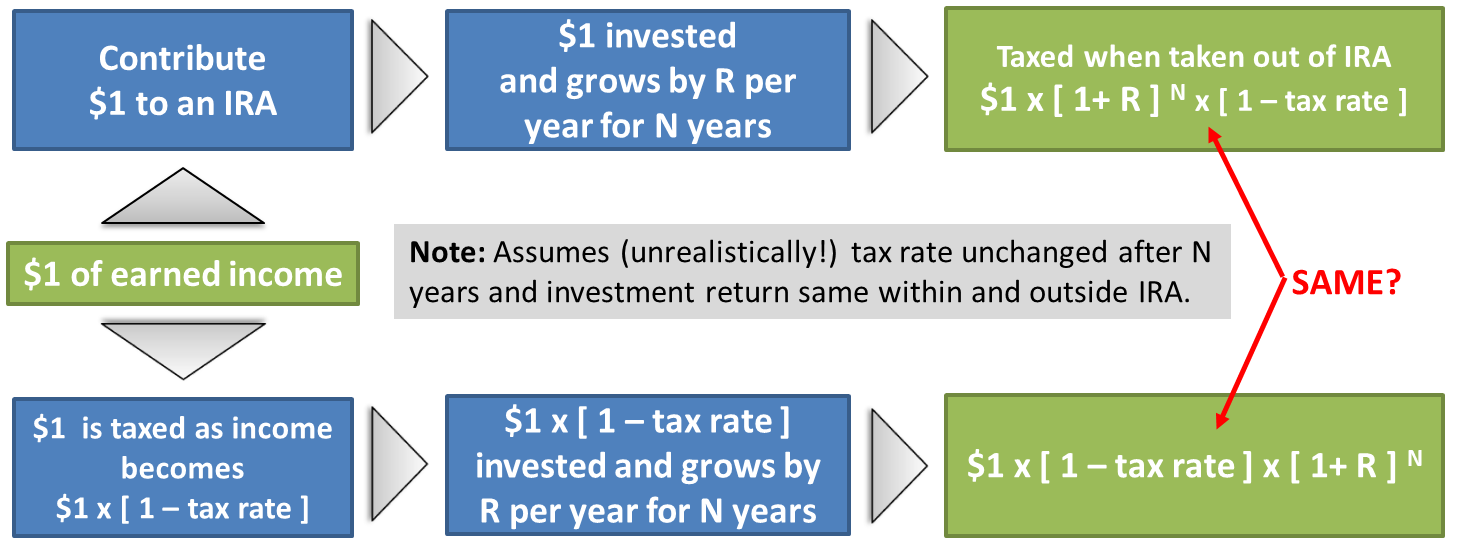

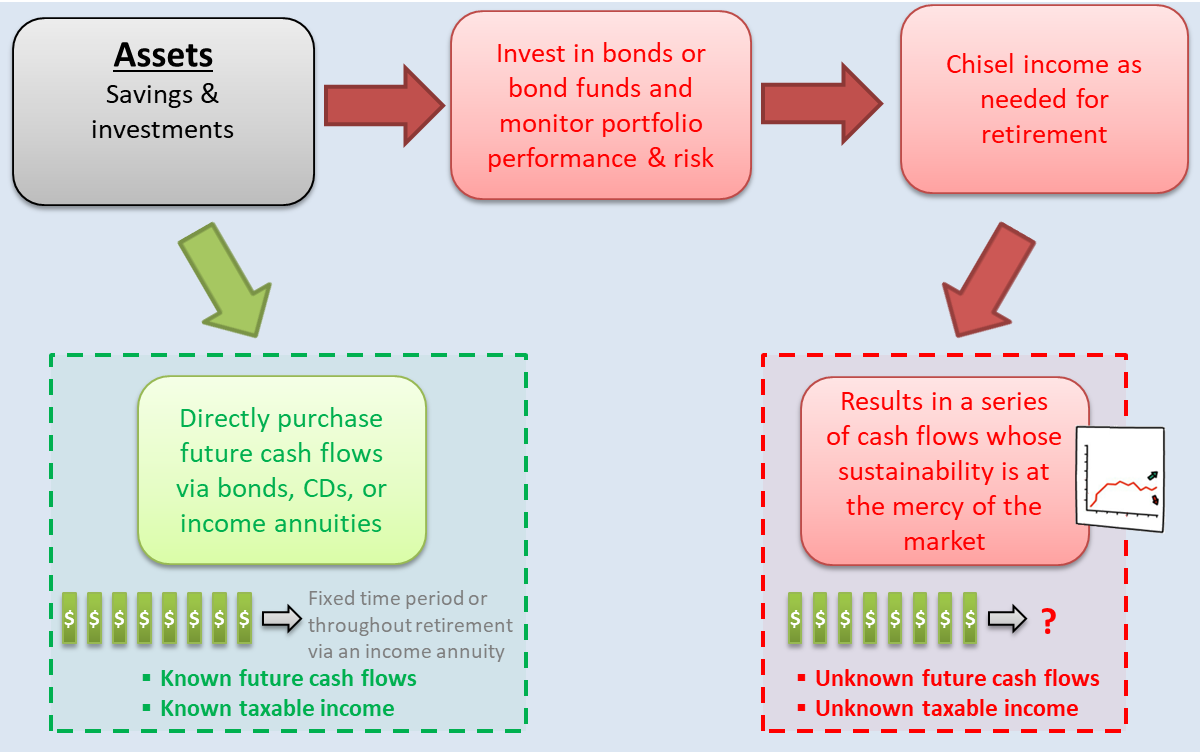

When it comes to investment strategies for retirement (and almost any other application), most individual and professional practitioners have adopted an approach based on total return investing and modern portfolio theory (MPT). So the natural income from the portfolio (e.g., dividends and interest) is typically reinvested and income required for spending is chiseled off from the portfolio as needed.

Portfolio volatility presents a risk as it can jeopardize one’s financial security in retirement by increasing the probability of running out of money (i.e., potentially less money to chisel from). For example, retirees may still need to withdraw from their portfolios during market declines and this would result in forced selling at depressed prices. Of course, conservative financial planning should allow for such situations and be able to withstand such scenarios.

This typically results in constructing a diversified portfolio that will offer an attractive balance of growth potential and risk. If we confine ourselves to a world with just stocks and bonds (for the sake of simplicity), then the idea would be for stocks to generate sufficient long term growth to help combat inflation or generate real returns while bonds might be regarded as a diversifying asset. As long as the bond allocation keeps up with inflation and tends to zig when stocks zag, many investors are content to maintain significant bond allocations in order to balance risk in their portfolios.

| Side note: Why do bonds typically exhibit lower returns and less volatility than stocks?

On the one hand, stocks are effectively perpetual securities and their dividends are not guaranteed. On the other hand, bonds ultimately mature and offer contractually guaranteed cash flows. Put simply, bonds offer more certainty than stocks. Thus, it is unsurprising stock prices tend to be more volatile than bond prices and investors label bonds as the safer investment.

Investment theory indicates higher returns are the reward for higher risk – assuming that risk is systemic and cannot be diversified away. In the US, this has certainly been the case historically with stocks handily outperforming bonds over the long run. So conventional wisdom holds that stocks should have higher expected returns than bonds over longer periods since they are more volatile.

This risk-based argument is presented from the investor’s perspective. What is less discussed is the flipside: the issuer perspective. That is, what about the perspective of the corporate or government issuers of securities? Let us take a corporation seeking to raise capital as an example. From their vantage point, issuing equity can be attractive in the sense that it does not impose any contractual payments (dividends, if any, can be skipped). However, if they issue a bond, then they will be obligated to make interest payments and repay the principal at maturity.

In this light, issuing equity imposes less financial constraint and may be viewed as a favorable option. Accordingly, they may be encouraged to issue equity rather than bonds. In turn, this could tip the scales of supply in demand in such a way to make stocks cheaper and more conducive to higher returns. |

The bottom line is that market risk is critical in the context of retirement planning. So the lower volatility and low to negative correlations with stocks can make bonds useful in maintaining a diversified portfolio. However, viewing bonds only through the lens of market prices ignores the inherent stability they can provide in terms of generating specific cash flows with little to no uncertainty (i.e., the same attribute that likely makes them less volatile).

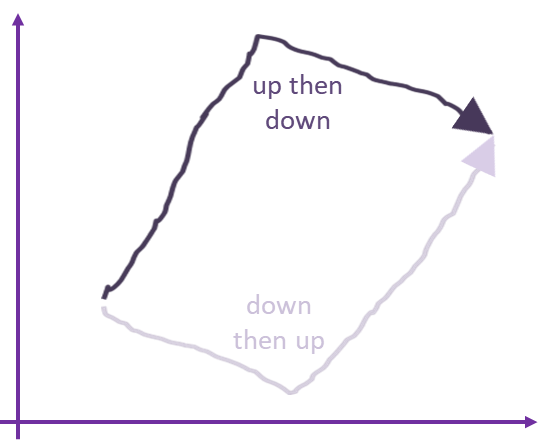

Let us take a step back and look at the bigger picture. Consider a retiree who wants to ensure their portfolio will provide adequate income as long as they may live. A portion of this income will likely come from their fixed income allocation. So they purchase bonds or bond funds, but only to observe them as squiggly lines on charts that may later be converted to cash. In other words, they purchase future streams of cash that could be used for retirement spending, but ignore those stable cash flows, reinvest them, and end up at the mercy of the market when they want to extract those funds down the road.

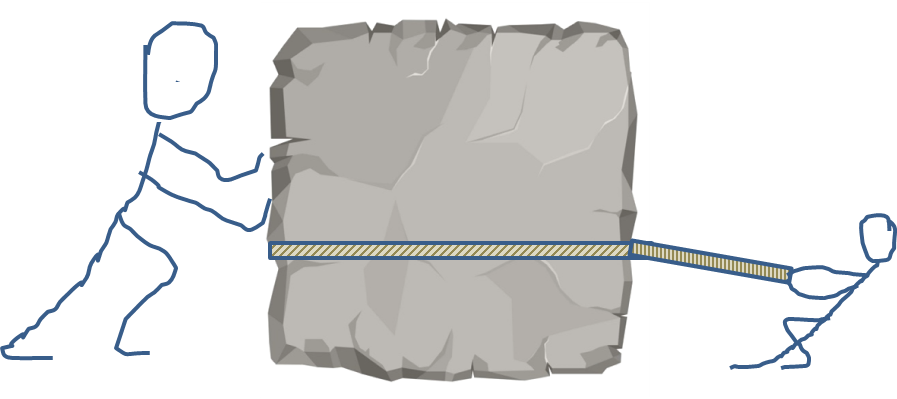

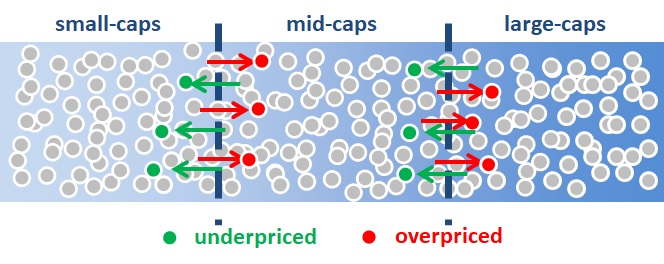

Figure 3: Roundabout way to create future cash flows

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

This seems a rather roundabout way of using bonds when the ultimate goal is income. Bonds and, more generally, fixed income investments already generate specific cash flows that are independent market risk when held to maturity. In my view, this is the real sanctity of fixed income investing. However, this notion seems to have been lost with many of the contemporary investment strategies that do not specifically align assets with liabilities comprised of future outgoing cash flows.

While the term fixed income is still widely used to describe various investments, it has lost the essence of its literal meaning. Hence this article and my goal to restore this sanctity of fixed income. The following sections discuss two specific tools investors can use to generate fixed cash flows and manage relevant risks: bond ladders and income annuities. While I touch on some of the potential cost and tax savings, I believe the greatest benefit is simplicity. In my experience working with many investors over the years, I find a greater understanding of one’s financial plan often facilitates the most peace of mind – regardless of the potential monetary benefits.

Bond ladders

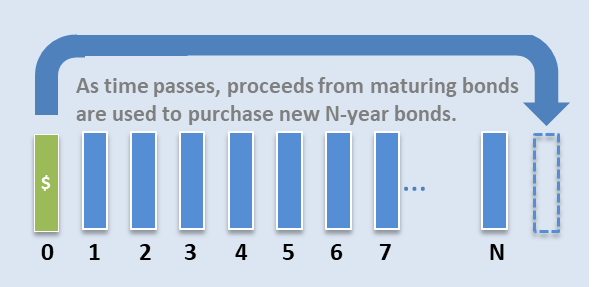

A bond ladder is basically a series of bonds spaced out over a specified time period (e.g., five, 10, or 20 years) and held to maturity. As time passes, each bond’s time to maturity decreases. In particular, the proceeds from each maturing bond are used to purchase a longer term bond to restore the original length of the ladder.

Figure 4: N-year bond ladder illustration

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

For example, let us consider a 10-year bond ladder comprised of 10 bonds – one for each year. After one year passes, the first one-year bond matures and the 10-year bond is now a nine-year bond. So the proceeds from the maturing bond are used to purchase another 10-year bond and we are back to a 10-year bond ladder again.

I may have brushed some of the details under the rug (e.g., callable bonds and defaults), but this describes the general approach. The process is simple and eliminates unnecessary turnover from any jockeying around. There are basically two moving parts: how long of a time period to use and how far to space bond maturities within the ladder. So let us consider what to consider when deciding how to structure a bond ladder.

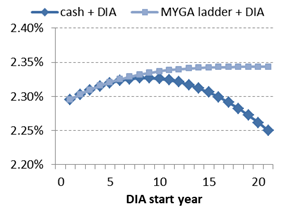

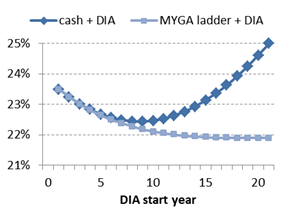

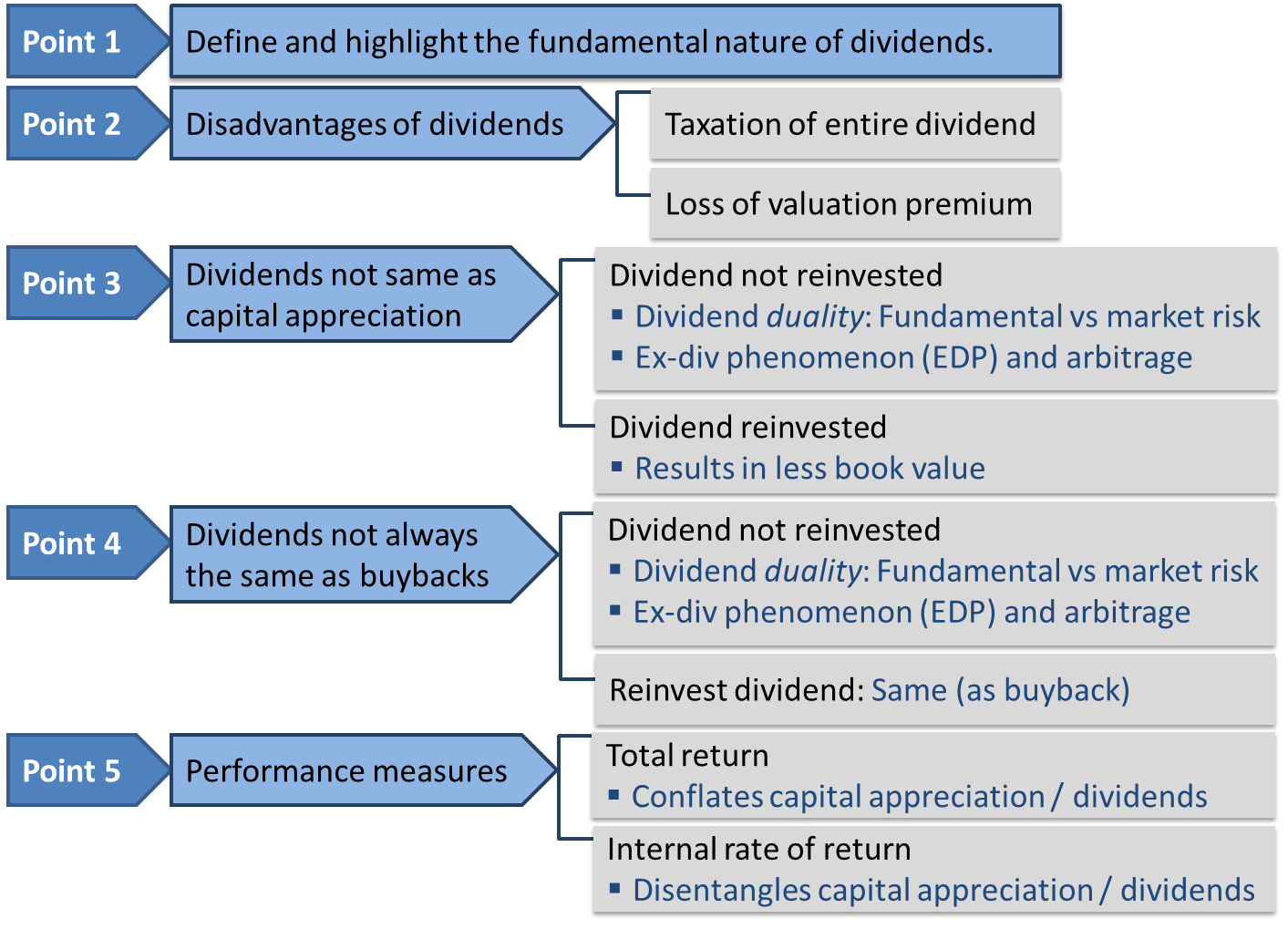

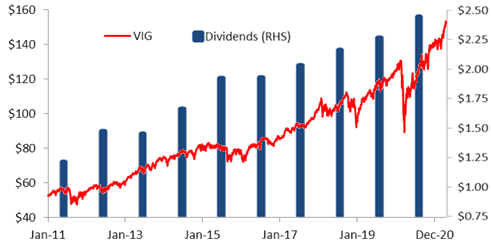

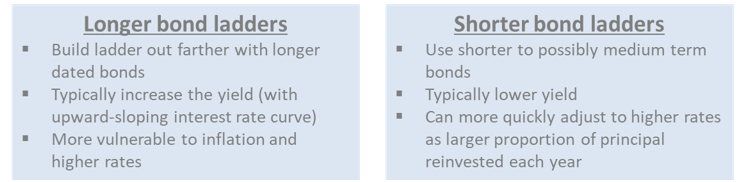

I find the main decision is how long to structure a ladder. Several factors are relevant here. In an environment with a typical upward sloping yield curve, longer ladders will naturally increase the yield. At the same time, this will also likely increase the volatility of the ladder’s market value and vulnerability to inflation. While many people consider volatility synonymous with risk, this could actually improve a ladder’s ability to diversify other positions (e.g., allocations to stocks).

Shorter bond ladders basically exhibit the opposite attributes. They generally have lower yields, are less volatile, and less susceptible to inflation. Indeed, as each year passes, shorter ladders would reinvest a larger proportion of their total capital (1 out of N bonds) and more quickly benefit from the presumably higher rates.

Figure 5: Bond ladder attributes

We could take this example to the extreme by considering a bond ladder with zero length. That is, the capital would simply be invested at overnight rates (like a savings account). On the one hand, it would not earn any term premium. On the other hand, it could instantly benefit from any higher rates due to inflation. This train of thought could be useful for retirees where inflation is a critical risk.Source: Aaron Brask Capital

We could take this example to the extreme by considering a bond ladder with zero length. That is, the capital would simply be invested at overnight rates (like a savings account). On the one hand, it would not earn any term premium. On the other hand, it could instantly benefit from any higher rates due to inflation. This train of thought could be useful for retirees where inflation is a critical risk.Source: Aaron Brask Capital

Of course, one could use different types of bond funds (long- vs short-term) to manage the above risks. However, I find the simplicity and passive nature of bond ladders attractive – especially when focusing on the income profile and its relationship with inflation. In my experience, both active and passive bond funds tend to have excessively high turnover. This jockeying around from one bond to another does not necessarily lead to any reliable benefits, but can impose additional fees and trigger sporadic capital gains.

Another application for bond ladders is one in which the actual bond principal is used for consumption. For example, consider a couple with one child entering college now and another starting four years down the road. In this case, they may wish to set aside funds to cover tuitions for the next, say, eight years. In this case, it is not just the bond income that is relevant as the principal will be spent as well. One might even use certificates of deposit (CDs) that accrue or fixed annuities, but do not pay any interest.

Retirees may also set up bond ladders with the intention of spending the principal as bonds and CDs mature. The obvious challenge in this scenario is not knowing how long to they will live. If they build a bond ladder out to their (actuarial) life expectancy, then they may live longer than average and have no more bonds maturing to fund their retirement. One solution is to plan for a reasonably long lifespan. However, this requires one of two things:

- More money to provide for those potential additional years of spending or

- Reducing the amount invested in each bond or CD which means less money for spending each year

On an individual basis, each retiree may effectively be forced to plan for the ‘worst-case’ scenario – living longer. For the lucky few that live like cockroaches, they will be happy they planned conservatively. For the majority who live shorter, average, or slightly above average lifespans, this conservative approach will result in their retirements being overfunded (only known in hindsight). Accordingly, this approach results in significant overfunding at the aggregate level – a natural byproduct of each individual’s desire to avoid running out of money. The income annuity products in the next section directly address this issue.

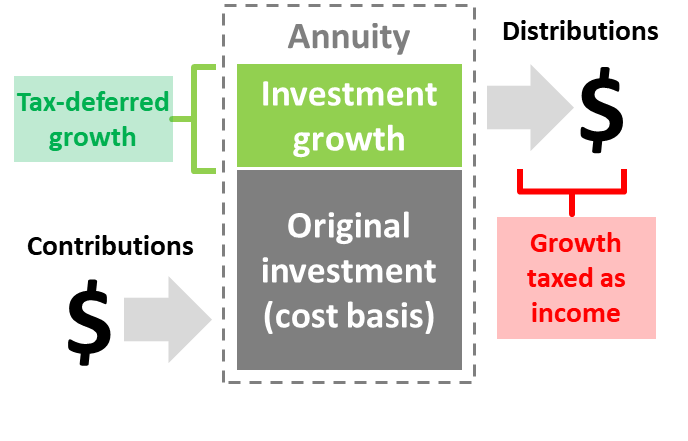

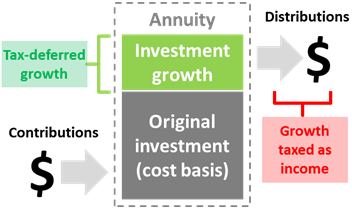

Income annuities

Simply put, an income annuity is a product offered by insurance companies whereby they allow individuals (or couples) to purchase income that is guaranteed to last as long as they live (e.g., throughout retirement). The amount of income relative to the purchase price is determined by a combination of actuarial (i.e., life expectancy) and market factors (i.e., interest rates). As of my writing, for example, a 70 year old male can purchase $1,443 in guaranteed monthly income for the rest of his life for $250,000. On an annual basis, this represents a payout of approximately 7%.

| Side note: Annuities are bad, aren’t they?

Annuities have rightfully earned a negative stigma from the agents pushing more expensive products with higher commissions. While I have written extensively on the drawbacks of variable annuities (e.g., excessive fees and potential tax issues), I find income annuities to be a very efficient tool for retirement planning. Unlike their complicated variable cousins, income annuities are very simple. This simplicity makes it easier for insurance companies to manage their risk. In theory, this should help to reduce their costs. Moreover, simplicity also makes it much easier for investors and independent agents (like myself) to compare apples with apples, shop around, and get the best rate. This comparison shopping imposes additional gravity on income annuity prices from competition.

In my experience, income annuities have become more competitively priced in recent years and this makes them an attractive option for many retirees. I built my own calculator to assess the implied costs embedded in income annuities for my clients, but online calculators are also available for those who know what they are doing (one example here). David Blanchett (Morningstar Investment Management), Michael S. Finke (The American College), and Branislav Nikolic (York University – Department of Mathematics and Statistics) published a recent article that corroborates my experience. Indeed, when normalizing for interest rates, they find the trend for income annuity prices was lower over the seven-year period ending in August 2020. In another article, Blanchett and Finke found that the rates offered by some multi-year guaranteed annuities (MYGAs) were more attractive than those with CDs, government/treasury bonds, and corporate bonds. |

Figure 6: Example income annuity illustration

As I highlighted in the previous section, individual investors generally cannot afford to run the risk of assuming they will only live to their actuarial life expectancy. Accordingly, they often play it safe by allocating enough money to fund retirement for a period that is significantly longer than their true life expectancy. So this results in overfunding at the aggregate level. This is where insurance companies can be helpful.Source: Aaron Brask Capital

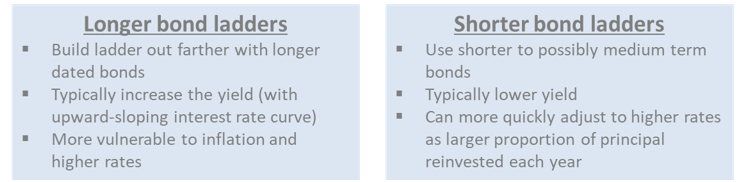

Unlike market volatility, actuarial risks such as lifespans are very predictable when averaged across large groups of people. By pooling risks across many annuity customers, insurance companies can effectively net out the longevity risks and price guaranteed lifetime income based on the average life expectancy. For individuals who would otherwise have to plan well beyond their life expectancy to be safe, pooling risk via an income annuity could allow them to free up capital or purchase a higher level of income per year.

For example, consider a 65 year old man with a life expectancy of 18 years (i.e., expected to live to 83 years old) deciding between a bond ladder and an annuity. Assuming the same level of annual cash flows, constructing a bond ladder out to age 90 would cost significantly more than an annuity based off of a life expectancy of 83. Indeed, the bond ladder would require funding 25 years (90 – 65) of cash flows whereas the annuity price would only reflect the average of 18 years. Ignoring the time value of money, the bond ladder would require approximately 39% (25÷18-1) more capital for the same level of cash flows.

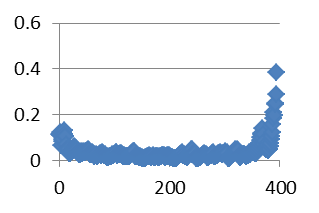

Figure 7 below illustrates the expected mortality rates for 65 year old males and females. As one might expect, very few people are expected to die early on, most will likely live to right around their actuarial life expectancy, and increasingly fewer will be expected to live each year further out. With a large enough group of income annuity purchasers, the shapes of these curves would directly reflect the actual outgoing cash flows. So an insurance company could purchase fixed income investments to provide for that cash flows.

While insurance companies are in business to earn a profit, any additional expense (above and beyond the actuarial fair price) paid by income annuity purchases would likely be significantly less than what it would cost for them to secure their own income through age 90, 100, or beyond – whatever age required to ensure the likelihood of running out of money was de minimis. The market jargon used to describe this averaging phenomenon is mortality credits. That is, income annuity clients who live longer effectively receive credits from those who live shorter lifespans.

Figure 7: Distribution of mortality rates

Source: Social Security Administration (2017 period life table)

Mortality credits alone can make income annuities an attractive tool for many retirees. However, I also like to present income annuities from another perspective. Given the current market environment where both interest rates and dividend yields are so low, most retirees will not be able to live off the natural income from their portfolios (i.e., dividends and interest). Accordingly, they will have to dip into principal to fund their retirement.

Once one acknowledges principal will be sold over the course of their retirement, they have a choice. One the one hand, they can wait and chisel as needed down the road. Of course, this leaves future income at the mercy of the market. Moreover, each time one chisels away from their portfolio, it will naturally reduce the dividend and/or interest income paid out in subsequent years. With less income, the shortfall could increase and require chiseling away even more principal. This can be a slippery slope.

On the other hand, one way to mitigate this risk could be to allocate a portion of one’s fixed income investments to a bond ladder or income annuity. Rather than being at the mercy of the bond market when chiseling off money for spending, an income annuity effectively allows one to pre-chisel income in advance – effectively eliminating the market risk for this stream of income.

Some other considerations with income annuities

In addition to fees (discussed in the shaded side note box above), another concern that periodically comes up is what would happen if one purchased an income annuity, but only ended up living a short period. If one paid a significant sum upfront for an income annuity, but only received a few payments in return, it would undoubtedly be negative economic outcome (and personal tragedy). However, most insurance companies will guarantee a 100% return of premium in exchange for reduction in payout. This is effectively a money-back guarantee – something most conservative bond funds cannot even offer. Given the low interest rate environment we are currently in, I find this option provides additional peace of mind – especially where children or other legacy concerns are present.

One approach many people choose is to allocate just enough to an income annuity to cover their basic necessities. More generally, I like to integrate income annuities into a broader plan for retirement income that complements the use of other assets and sources of income while tending to the potential risks that could jeopardize retirement security (inflation, healthcare needs, etc.). In addition to being able to provide guaranteed income, options like the cash refund feature described above, the ability to structure income via joint and survivor payouts for couples, and other features can make income annuities a versatile tool for retirement planning. This versatility can be especially useful for minimizing tax impact with retirement. I do not elaborate on the taxes here, but I wrote another article on precisely that topic: Optimizing Tax Benefits with Annuities.

One last word on annuities (and life insurance)

Without doubt, the topic of annuities is often polarizing and many of the stigmas attached to them are for good reason. Having worked with individuals and families over the last decade, I have seen the good, the bad, and the ugly sides – including, but not limited to misleading sales pitches, excessively high commissions, tax inefficiencies, and poor performance. In other words, the standard of care under which annuity and insurance products are sold appears to fall short of the fiduciary standard.

I like to think my approach is different. While I uphold a fiduciary standard in all of my dealings with clients, I believe my PhD in mathematical finance, actuarial background, and Wall Street experience advising insurance companies make my perspectives on planning, investments, annuities, and life insurance truly unique. Moreover, I offer my clients multiple options: hourly/fixed-fee financial planning services, traditional fee-based portfolio management services, and income annuities (which are not necessarily mutually exclusive). By highlighting the risks, costs, and performance of each approach, I view my role as educating, guiding, and executing where applicable.

Put simply, I find there can be immense value in pre-chiseling income upfront via bond and CD ladders or income annuities. By combining this guaranteed income with other sources of income (social security, dividends, etc.), I can often structure portfolios in such a way to generate sufficient income naturally. I may be shooting myself in the foot to some degree, but I find this type of upfront planning can mitigate, if not eliminate, the need for ongoing portfolio management. As a result, this can significantly reduce both costs and taxes in many cases – thus allowing clients to spend more or leave larger legacies to their heirs.

Notwithstanding these benefits, I find the biggest benefit of this strategy is its simplicity. This building blocks approach to income is very intuitive and I find clients just get it. While this article focused on retirement income, this approach can also be used with trust planning for blended families and other situations where delineating income and principal is helpful.

Concluding remarks

I believe the true sanctity of fixed income lies in the ability to purchase specific cash flows in the future with precision and certainty. However, I believe this has become a lost art and the phrase fixed income has lost its literal meaning.

The primary benefit of fixed income assets is now seemingly derived from market prices being less volatile than or less correlated to other asset classes. Indeed, many market practitioners focus on modern portfolio theory and total return investing where all portfolio income, regardless of how robust or certain it may be, is indistinguishable from capital appreciation.

This article highlighted how we could restore the sanctity of fixed income via examples with bond ladders and income annuities. In particular, I highlighted the context of retirement income. Regardless of whether one is already retired or not, the focus of saving and investing ultimately becomes generating adequate income during retirement. In this context, I believe that purchasing future cash flows with certainty can be immensely helpful.

For many, this approach may not meaningfully alter their allocations or economic exposures. If retirees were to look inside bond funds they own, then many might find the cash flows of the bonds they already own create a ladder of future cash flows they could use for retirement income planning. However, bond funds have notoriously high turnover and many of those bonds will not be held to maturity. As a result, many of those cash flows will be sold before they end up in the hands of investors who could use them.

Other articles that may be of interest:

Disclaimer

- This document is provided for informational purposes only.

- I am not endorsing or recommending the purchase or sales of any security.

- I have done my best to present statements of fact and obtain data from reliable sources, but I cannot guarantee the accuracy of any such information.

- My views and the data they are based on are subject to change at any time.

- Investing involves risks and can result in permanent loss of capital.

- Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results.

- I strongly suggest consulting an investment advisor before purchasing any security or investment.

- Investments can trigger taxes. Investors should weight tax considerations and seek the advice of a tax professional.

- My research and analysis may only be quoted or redistributed under specific conditions:

- Aaron Brask Capital has been consulted and granted express permission to do so (written or email).

- Credit is given to Aaron Brask Capital as the source and prominently displayed

- Content must be taken in its intended context and may not be modified to an extent that could possibly cause ambiguity of any of my analysis or conclusions.

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

We could take this example to the extreme by considering a bond ladder with zero length. That is, the capital would simply be invested at overnight rates (like a savings account). On the one hand, it would not earn any term premium.

We could take this example to the extreme by considering a bond ladder with zero length. That is, the capital would simply be invested at overnight rates (like a savings account). On the one hand, it would not earn any term premium.