Here is a link to the article

PDF .

| In my last job with a large investment bank I built two global research teams and worked with high-profile clients around the globe. Having left the big leagues to start my own firm, my clients are more diverse in terms of wealth. While I still work with some high-flyers, I mostly work with the mass affluent or millionaire-next-door types (but also some less fortunate families). To convey my previous experience when meeting new prospects, I would sometimes say “I used to work with billionaires, but now I work with millionaires.” Then someone asked me what I did to them.

Humor aside, my experience has helped me understand the varying degrees of desire and need for returns among different types of investors. All else equal, virtually everyone prefers higher rather than lower returns. However, the prudence of pursuing higher returns depends on the financial situation and goals of each individual or organization.

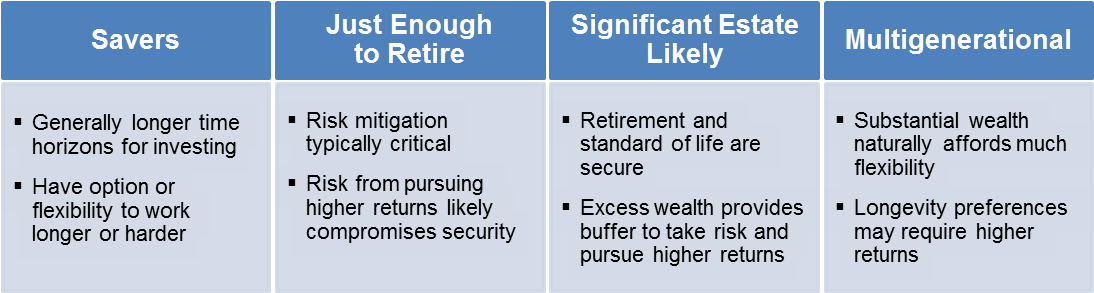

This article focuses on the relevance of returns for four types of investors: those saving for retirement, those with just enough to retire, those likely to leave behind a significant estate (for heirs, charities, etc.), and those with multi-generational goals for substantial wealth. For each investor type, I consider how relevant higher returns are to achieving their goals and the role their preferences may play by potentially imposing additional constraints.

On balance, I find the need or preference for higher returns generally increases with the magnitude of wealth. This is due to two primary factors: an increased capacity to assume risk and the amplification of returns over longer time frames. I discuss the nature of this trend across the wealth spectrum. In the case of substantial wealth, I quantify the need for returns and present a model for analyzing multi-generational investment goals. This provides a sensible and intuitive framework for assessing their investment strategies. My model indicates multigenerational wealth effectively needs to pursue higher returns via higher equity allocations in order to accommodate familial growth and combat inflation. |

Figure 1: Factors Related to Pursuing Higher Returns

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

Overview

There are two key ingredients for most investment-related marketing pitches: return and risk. Some advisors will tout the performance of a particular investment. Others will focus on the conservative or low-risk nature of an investment – perhaps even guaranteed returns. All else equal, higher returns and less risk sound great. However, it is critical for investors to understand the importance of returns and risk in the context of their broader goals (as well as the certainty of the fees) involved in pursuing various strategies. These considerations can impact many decisions around the investment process including:

- Advisor engagement (if any): Type of advisor, services, compensation structure, etc.

- Financial plan and investment strategy: Asset allocation, source of retirement income, etc.

- Choice of actual investments: Funds, individual securities, active or passive, etc.

- Performance and cost: All of the above will impact overall performance and costs.

This article addresses the relevance of higher returns for different investors and is organized in two parts. Part I contains three sections discussing several factors involved in balancing risk and returns. The first section focuses on two key components of risk that can determine one’s success or failure in achieving their goals. The second section highlights three primary strategies for achieving higher returns. The third section discusses the concept of need versus preference when it comes to returns.

Part II contains four sections – one for each investor type. Based on the perspectives highlighted in Part I, I discuss the relevance and risks associated with pursuing higher returns for each type of investor.

Part I: Risk and Returns

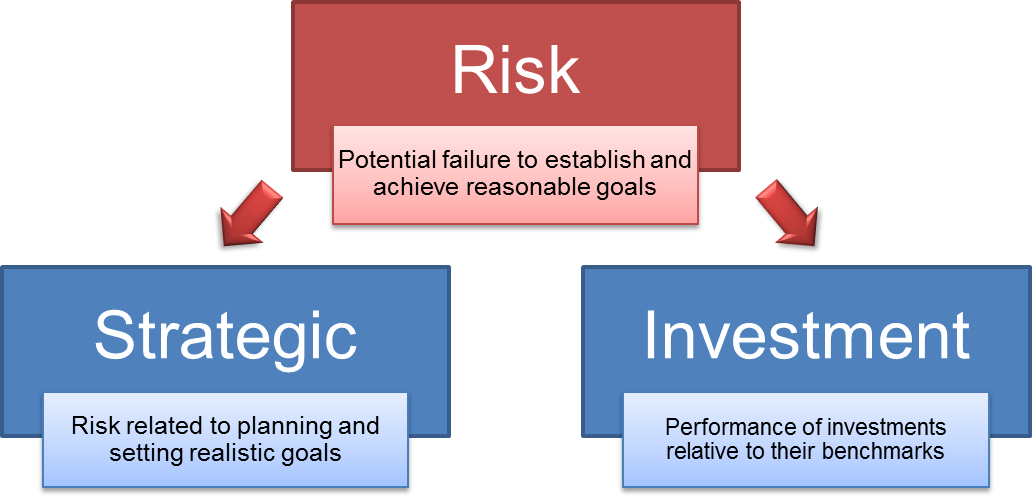

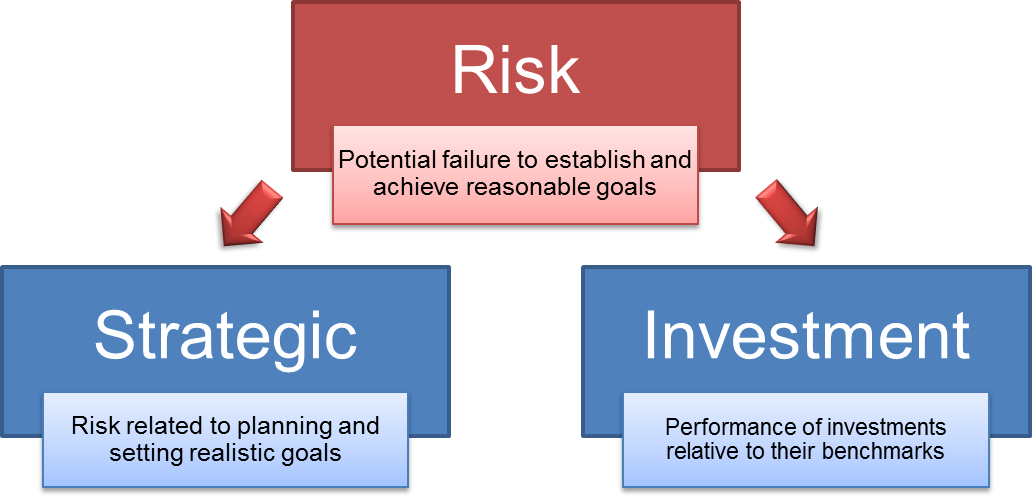

1 – Dimensions of Risk

At the broadest level, I think of risk as anything that can result in one’s failure to establish and achieve reasonable goals. In the context of investments for individuals or families, these goals typically relate to their retirement, standard of living, and objectives related to their legacy (e.g., heirs and charitable causes). Given the importance of and widespread need for retirement planning, this will be the default focal point (unless otherwise stated) of this article.

I divide risk into two primary components: strategic and investment risk. Strategic risk involves the setting of realistic goals. In order to set realistic goals, one must estimate both the income required to support one’s goals as well as investment returns for various types of assets (e.g., stocks and bonds) over a typically longer term horizon (e.g., 30 years). Given the uncertainty around future spending and market returns, it is naturally important to pursue a conservative approach in both these endeavors.

Figure 2: Decomposing Risk

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

One facet of strategic risk relates to the investor’s risk profile. For example, some investors simply cannot tolerate much volatility. Accordingly, financial plans involving heavy equity allocations or insufficient allocations to less or negatively correlated assets (e.g., hedge funds) can make the investors so uncomfortable they abandon the strategy at an inopportune time (i.e., sell stocks after a period of volatility where prices have fallen significantly). A similar argument can be put forth for tracking error. If, for example, the S&P 500 has gone up by 10% but their value-based portfolio was flat or down, then an investor may feel left out of the market’s gains and want to jump ship.

The second component of risk relates to investment risk. Once one has crafted a realistic plan or strategy and identified the guidelines for their allocations to various asset classes, one must execute the investment strategy. This typically translates into selecting managers and products (e.g., investment funds) to fulfil the plan’s allocations. Assuming the return forecasts were reasonable, investment risk surfaces when a manager or product deviates significantly from their benchmark.

For example, an equity fund manager pursuing a value strategy might fall in love with some particular investments and drift into a growth strategy (in order to hang on to those stocks that are no longer value-oriented). This style drift can have an adverse impact on the overall financial plan by changing the overall asset allocation. Given that each plan is based on varying degrees of diversification, an unexpected concentration in a particular asset class, sector, or style can introduce additional risk and jeopardize the original goals.

On balance, different investments lead to different results. It is important to align the investments with the needs and preferences of investors. A significant part of this involves management of expectations. Regardless of the risks one is taking, (e.g., stocks, bonds, growth, international, etc.), it is a good idea to make sure investors are comfortable with the overall level of anticipated volatility and/or tracking error so market performance will not catch them off-guard and make them question their strategy.

| A Word on Fees and Taxes

I do not delve into the issue of fees as they are a certainty, not a risk. In my view, the real risk with fees is whether a particular investment or product provides performance commensurate with the fees. Many strategies have been commoditized and are available in low-fee index funds. So it is important to weigh how likely more expensive funds will outperform a similar fund with lower fees.

Note: Many people attempt to minimize fees based on the belief that all else is equal. However, all else is not equal. For example, some index products offer better exposure to factors such as value (that I believe will more than earn their fees over the longer term) and are well worth the higher fees .Moreover, the mechanics of many low-fee index products embed subtle costs related to their performance. For more information on this topic, please read my article Index Investing: Low Fees but High Costs.

I also do not discuss taxes in this article. They are, without question, a critical consideration for financial planning and wealth management. The tax implications of financial plans and investment strategies should be discussed with a qualified tax professional. |

2 – Strategies for Higher Returns

For the context of this article, I highlight three particular strategies for targeting higher returns relative to a standard 60/40 portfolio (there are more, of course). Each of these strategies involves different risks and none can guarantee higher returns. In the following, I discuss the upside potential and downside risks of each strategy.

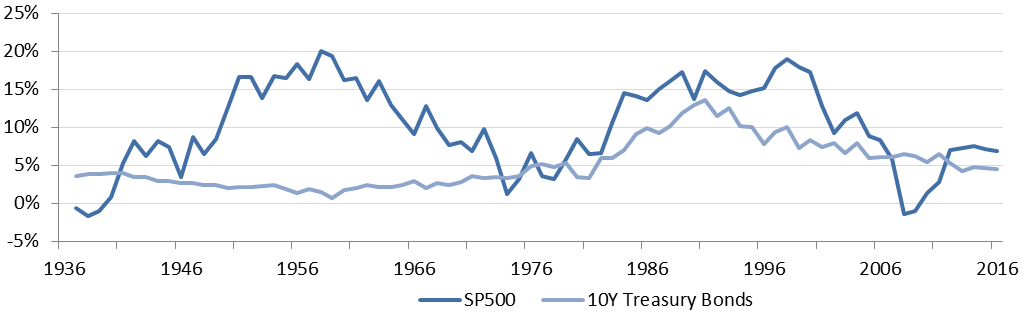

Increased Exposure to Equities

Equities have historically provided higher returns relative to bonds. Of course, there have been periods (sometimes very long) where bonds outperformed equities and there will more periods like this in the future. Periods like these confuse and intimidate many investors, but I expect this trend to continue as survival instincts and the pursuit of profit will keep capitalism alive and continue to give stocks a strong edge over the long term. For more information on why I believe this to be the case, please read my article on Asset Allocation where I also quantify the upside benefits of higher equity allocations.

| In the 20th century, the United States endured two world wars and other traumatic and expensive military conflicts; the Depression; a dozen or so recessions and financial panics; oil shocks; a flu epidemic; and the resignation of a disgraced president. Yet the Dow rose from 66 to 11,497.

|

|

The primary risk of owning stocks is higher volatility. In some cases, investors simply do not have the stomach for the volatility. Even when they can tolerate the volatility, the volatile nature of stocks can make them inappropriate. For example, some investors simply cannot afford to take the risk since it may place them at a higher risk of premature wealth depletion.

Security Selection (Factor Tilts)

| Note: I only discuss equity factors here. There are factor models for bonds as well, but research indicates the higher volatility in equities creates more opportunity for factor models. |

The second strategy for targeting higher returns is to invest in equity managers or funds that tilt their portfolios toward factors that have historically increased returns and are likely to do so going forward (e.g., value). In the case of factor tilts, outperformance largely stems from:

- Behavioral issues: For example, investors tend to overpay for glamour stocks and divest fallen angels.

- Risk aversion: Some factors involve significantly higher volatility or tracking error. So outperformance is viewed as compensation for increased risk.

- Market mispricing: Recent research indicates the outperformance of many factors does not necessarily stem from higher risk. In other words, many securities are simply mispriced.

While technology and awareness might reduce the outperformance going forward, I do not believe it is likely to disappear since some of the reasons behind the outperformance are not likely to go away. In other words, risk perceptions (aversion) and human nature are not likely to change.

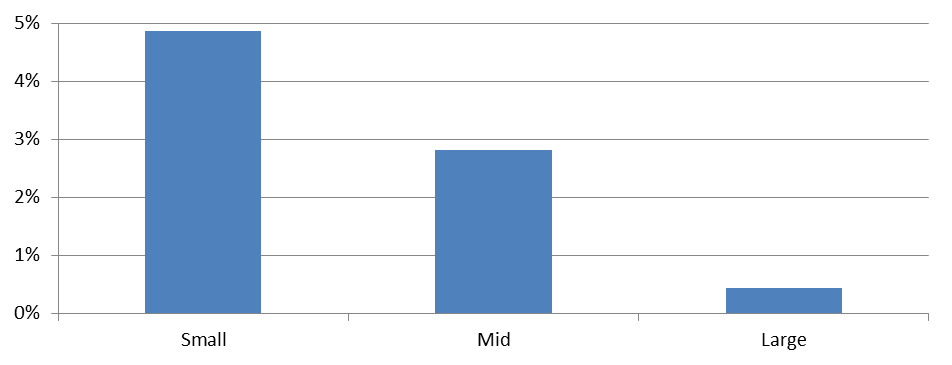

Just as I discussed with stock and bond performance, integrating factors does not always result in higher returns. However, I do believe value and other tilts (e.g., small size, quality, and momentum) will very likely result in better performance over the longer term. Of course, one must always weigh the fees against the likelihood and magnitude of outperformance.

Fees aside, some factor tilts add more volatility. Depending upon the correlation of the factor with the overall market, this could increase or decrease the absolute volatility level of the overall portfolio. This is an important consideration.

Factor tilts also introduce tracking error relative to the overall market. This is by construction since tilting or altering a portfolio away from the market portfolio makes it different than the market. Therefore its performance will differ from the market’s performance. As I mentioned above, sometimes performance will be better and sometimes it will be worse than the market. Investors who scrutinize risk through the lens of tracking error will have to consider this angle.

I believe there is a variety of managers and products that integrate factor tilts that are well worth their fees. Even if the outperformance and fees were a wash, sensibly utilizing factors can create more diversification within a portfolio. On balance, I find the marginal increase in fees required to integrate factors is a sensible and efficient means of targeting higher returns.

Risk Transfer

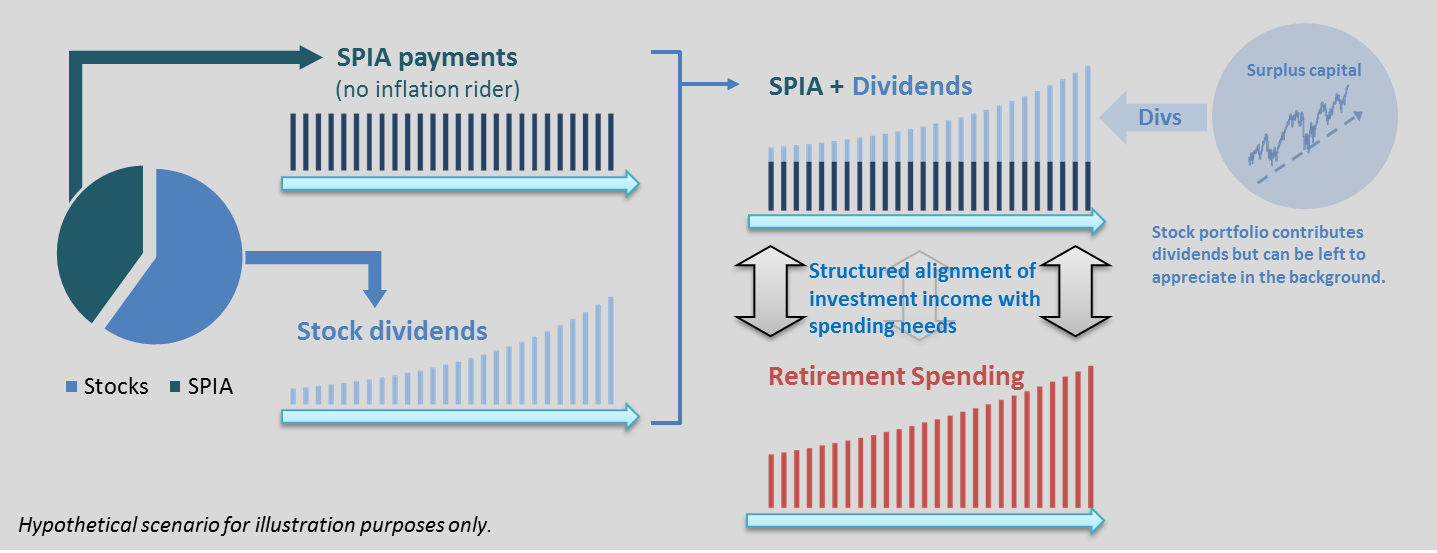

While the first two approaches are fairly well-known, I believe this third strategy to target higher returns, while little-discussed, offers a potentially more efficient and convenient approach for many investors to target higher returns while securing the income needed for their retirement.

The idea is to transfer risk away from the retirement income and concentrate it where it can be best rewarded. The best way for me to explain this phenomenon is to highlight two issues with the standard 60/40 approach and explain how my alternative structured approach to income can mitigate or avoid them.

In a typical 60/40 approach, synthetic income is generated by selling off parts of the portfolio. During turbulent periods, there can be a negative impact from selling off holdings when their prices are depressed. Of course, the converse is true as well; selling holdings when their prices are inflated can be beneficial. However, the net effect is negative and can dampen performance significantly over the long term. I provide a more detailed discussion and quantify this in my article on Structured Financial Planning. My primary point is that this standard 60/40 approach is highly dependent on market performance and market volatility can systematically dampen performance.

Another related issue with the standard 60/40 approach stems from the fixed nature of the stock and bond allocations. Maintaining fixed allocations requires rebalancing as markets move. Due the typically higher returns on the equity side, this process is generally asymmetric; it tends to redistribute the upside from the equity side over the bond side. In other words, it constrains the performance of the faster growing asset by trimming its allocation when its growth gets too far ahead of bonds. I discuss this is greater detail with my Asset Allocation article.

One way to address these issues is to build a portfolio where the investor can live off of the dividends and interest. In other words, construct a portfolio where they did not have to chisel off parts of the capital to support their retirement budget. Given the currently low interest rates and dividend yields, this requires a significant amount of wealth. For example, $100k of annual spending would require $5 million invested in a stock portfolio yielding 2% and/or 10-year equivalent bond fund.

Many investors and investment professionals apply a rule of thumb to the 60/40 portfolio approach. They assume investors can withdraw 4% of the portfolio value in the first year and then increase that dollar amount by inflation in subsequent years without depleting their wealth over 20-40 year horizons.

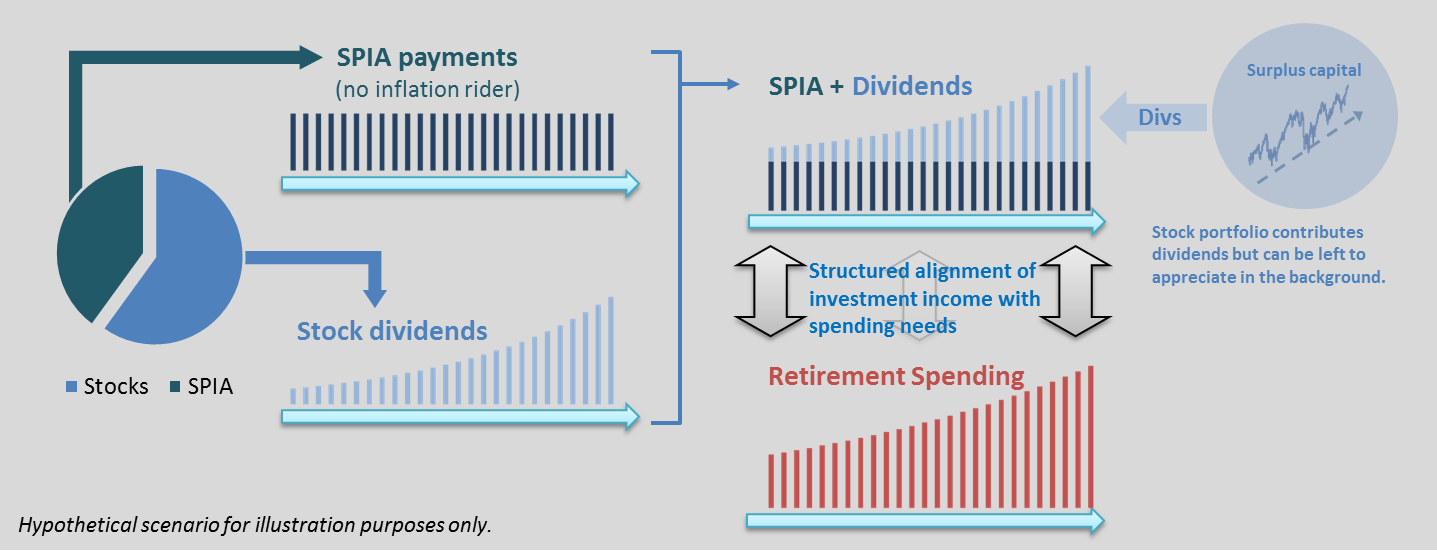

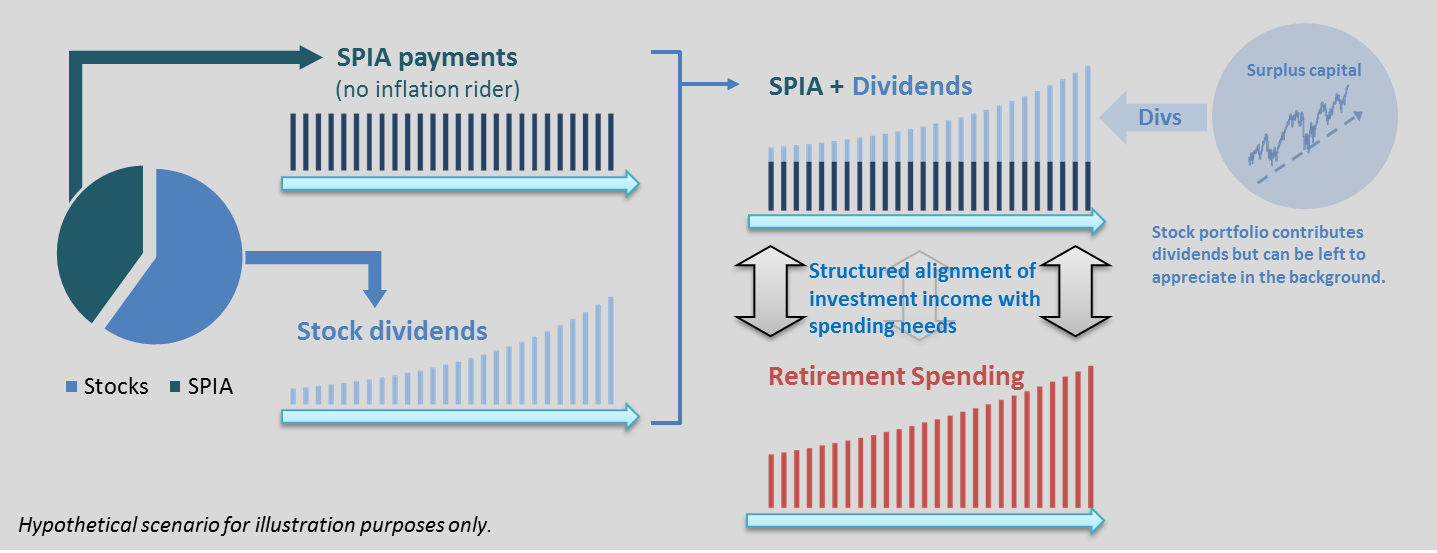

Figure 3: Structured Investment Income

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

So how can we close the gap between the 4% rule of the standard 60/40 approach and the 2% natural yield of stocks and bonds? One way is to take the 40% that would be invested in bonds and allocate it to a single premium immediate annuity (SPIA). As I discuss in my Structured Financial Planning article, SPIAs are really basic annuity products (investor gives cash to the insurance company in exchange for lifetime monthly payments). Moreover, they are typically competitively priced and embed little fees unlike many of the more complex annuity products.

Let’s consider a $1 million portfolio. If 40% or $400k is invested in a SPIA yielding 7% per year for the remainder of one’s life, this will generate $28,000 per year. With the other 60% or $600k invested in stocks, this will create an additional $12,000 of dividends per year. In total, this portfolio generates $40,000 per year between the SPIA and the dividends. Moreover, the dividends will typically grow at a rate that is greater than inflation. So we have generated an income stream that effectively replicates the 4% rule. There are several benefits to structuring a portfolio in this way relative to the 60/40 approach:

- Risk transfer & reduced market dependence: Retirement income is generated naturally in this framework, so investors do not need to access the capital portfolio. Accordingly, they are more immune to market fluctuations. The market risk is effectively transferred to heirs, charities, and other beneficiaries of the legacy portfolio.

- Transparency: This more structured plan makes it clear where income is coming from and delineates the income from the capital growth.

- Lower fees: An investor does not need to pay advisor fees on the SPIA allocation and the SPIA does not charge management fees like a bond fund or manager would.

- Maintenance: Depending on how the equity portfolio is managed, there can be little to no maintenance required. A set-it-and-leave-it plan could invest in a static basket of stocks or low-fee stock funds to bring the costs to almost zero.

- Unconstrained growth: The equity side of the portfolio is no longer trimmed and reallocated to the bond side. It can be left to grow unconstrained.

I have brushed many details under the rug here but I provide a more detailed discussion in my Structured Financial Planning article.

| Note: I am a fee-only advisor and not a licensed insurance agent. I cannot sell nor receive commissions for recommending these products. I say this only to disarm the reader since there are conflicts of interest with many financial professionals selling or recommending annuity products. That is, their advice could be influenced by the commissions they receive when selling these products. Mine advice is not tainted in this way. |

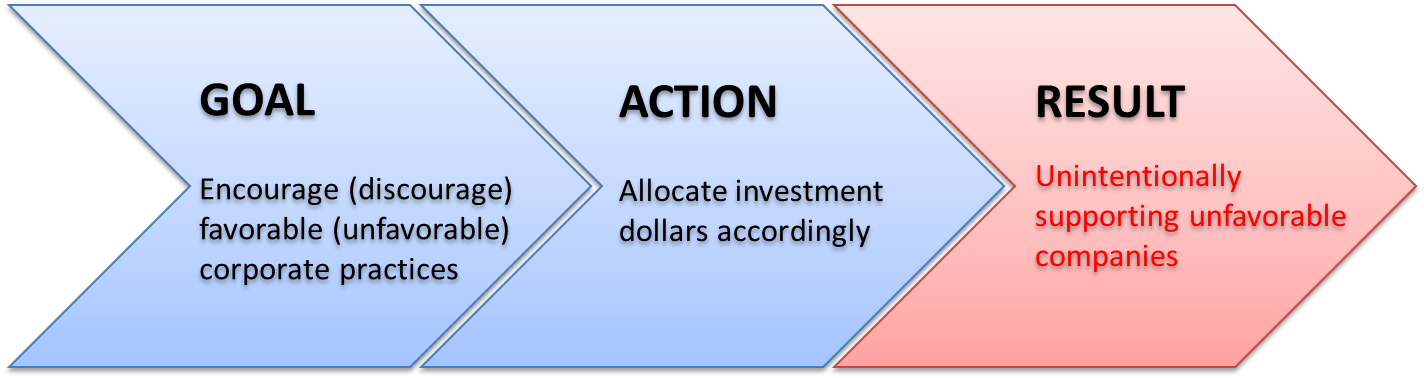

3 – Quick Word on Needs versus Preferences

I believe advisors should make it clear to their clients which investments and strategy are needed and which are not. Once the needs are reasonably covered, investment strategy should involve a balance of protecting and growing the excess wealth for legacy purposes (e.g., heirs and charities). That is, an investor’s preferences only become relevant once their needs are covered.

An investor’s needs can directly require or prohibit the pursuit of higher returns. In some cases, investors will need the extra returns to achieve some long term goals. In other cases, some investments or strategies introduce risks that unnecessarily compromise an investor’s plan or goals and are thus inappropriate.

It is worth noting there is naturally some gray area between needs and preferences. For example, does one only consider needs in the context of the current owner of the wealth? Taking this further in the case of multigenerational wealth, where does one delineate needs from preferences? Is it the third or fourth generation down?

From the standpoint of investment management, needs translate into constraints. For example, securing future liabilities requires more capital allocated to typically lower growth fixed income investments. Accordingly, hedging these liabilities means less capital allocated to more volatile but higher growth assets like stocks.

When it comes to preferences, each investor’s unique experience and investing history has helped them formulate their own set of perceptions. Moreover, their personalities and instincts can also influence the way they perceive investments. These can translate into guidelines or constraints for the types of portfolios and strategies they wish to pursue. Good advisors will attempt to educate their clients and provide them with a broader context. In reality, each individual’s experience is really just a blip in the grander scope of investing history.

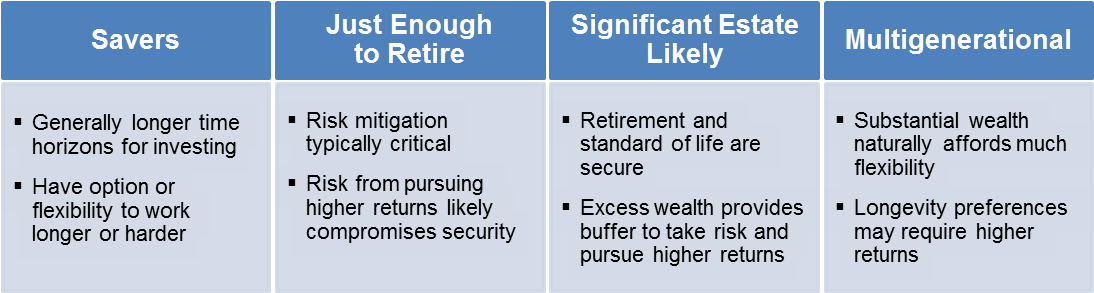

Part II: Relevance of Returns

In the following, I pull together the perspectives I highlighted in Part I about risk and return in the context of four investor types: those saving for retirement, those with barely enough to retire, legacy-minded investors with significant excess wealth, and those with multigenerational wealth.

Savers

If one is working and saving, they are likely headed toward a situation resembling one of the next two categories. While much of the logic I discuss for those two investor types will apply here, there are a few key differences. First, the time horizon for the investments is naturally longer and there will likely be little or no need for liquidity (access to savings and investments) while one is still working. In most cases, this will result in a higher allocation to equities and or factor tilts.

The second difference for savers is their flexibility around timing their retirement. In some cases, their financial situation may force them put off retirement and work longer to build a sufficient nest egg. Others may have more flexibility. Even when it is not necessary, some may choose to work longer. They might want to increase their standard of living or leave more to their heirs and charities. Some may simply enjoy their work or be reluctant to let go of a significant earnings stream.

In almost all cases, the option to work longer can create some additional flexibility and this can be reflected in the types of investments and strategies. For example, someone who enjoys their work may be inclined to take more risk on the investment side since they would not mind postponing retirement.

Just Enough

Planning for the just enough crowd is typically the most straightforward because needs dictate the types of investments or strategies that are viable. More volatile investments are generally not compatible with these retirees as they can introduce unnecessary risk that compromises financial security. In particular, there is little or no buffer saving that can cover potential investment losses. So certainty is the friend of an investor who has just enough to retire. In my experience, low-cost bond funds and annuities (e.g., the SPIA discussed earlier) are the most appropriate types of investments.

Significant Estate Likely

I find this situation interesting for at least two reasons. First, the very fact that there will likely be excess wealth means there is a significant buffer for risk. This opens the door to more investments and strategies. Second, the excess wealth is typically inherited by the children or put to use for charitable causes. These beneficiaries are more tangible in a sense whereas multigenerational wealth is less so. It typically benefits many people who are not yet known or even born (i.e., future spouses and children). Anyone who has been involved in constructing a long-term dynasty trust may recall the cold or impersonal nature of its rules and directives.

The likelihood of excess wealth creates a buffer with which one can assume more risk. In other words, their needs will not necessarily dictate the planning as with the just enough crowd. Accordingly, preferences become more relevant and this naturally creates additional flexibility. Assuming retirement needs have been sensibly secured, one might begin to think about integrating the goals, needs, or preferences of the beneficiaries.

In some cases, beneficiary goals may be more specific (e.g., special needs children). However, in most cases they generally amount to more is better. Given this general objective and the typically longer time horizon before the money is bequeathed, this situation allows for reasonably aggressive investment strategies. All else equal, I would typically encourage higher equity allocations and increased targeting of factors.

Of course, investors have their own preferences. Sometimes they will still want to minimize market volatility. They may simply not have the stomach to tolerate much volatility even when they believe it would likely increase their returns and the amount of money they pass on without necessarily threatening their retirement. Sometimes the optics of volatile brokerage statements is too much.

What is sensible to some is not to others. Indeed, there are many investors who are happy to take more risk once they believe their retirement is secure. Some may even have a natural inclination to take more risk (e.g., gambling instinct) and push the limits with their allocations or even leverage. At the end of the day, it is the job of the advisor to help each client construct a strategy and select investments that align with their goals and preferences.

On balance, I believe investors who are likely to leave behind legacy wealth should generally target higher equity allocations. Moreover, I view sensible factor tilts as an almost no-brainer option. As a highlighted above, I find the potential upside of integrating factors such as value, quality, small size, momentum, etc. is well worth the additional costs, volatility, and tracking error relative to a broad market equity portfolio.

I also believe my structured investment income approach is ideal for investors in this situation where the wealth will span precisely two generations. It clearly delineates wealth that will support retirement income needs from the excess wealth that will be passed on to heirs or given to charities. Implicit in this strategy is a transfer of market risk away from the retirement income and to the heirs and other beneficiaries. This concentrates risk in the area where it will best be rewarded (the equity market). Moreover, it still allows the investor to access the principal should an emergency or unforeseen even surface.

| Note: The distinction between those likely to leave a significant estate behind and those with more multigenerational mindsets is gray. In the former case, one could decide to leave less to their children and divvy up more of their estate amongst future generations. In practice, there is a balance between the cost of setting up multigenerational trusts and the magnitude of impact for each of the beneficiaries. Slicing the pie into small morsels simply may not be worth the effort. |

Multigenerational Goals

| Disclaimer: I am not a tax or estate planning expert. One should always seek advice from a qualified attorney and CPA for multigenerational planning endeavors. The views I discuss here strictly relate to investments and the scenarios are hypothetical in nature. |

Multigenerational wealth is interesting in that it naturally affords much flexibility in the context of its owner’s needs, but there are often strong preferences that can impact one’s overall strategy. In particular, families tend to limit future generation’s access and distributions – presumably to extend the longevity of the wealth. Given the longer time horizons associated with multigenerational wealth, time naturally amplifies the impact of returns. Figure 4 below illustrates this phenomenon over various time periods.

Figure 4: Compounded Returns

Period (years)

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

Simplifying many of the planning details (e.g., administrative costs and professional fees) and brushing the complexities of tax and estate planning under the rug, there are three primary moving parts in a multigenerational wealth plan: the amount of wealth distributed or consumed per unit time, the investment performance, and the longevity of the wealth. There is some flexibility in balancing these factors and it is the job of an advisor or family office to assess each client’s preferences.

Consumption

In terms of consumption, wealth may be distributed to various beneficiaries such as charitable causes, family, or foundations (that could potentially employ family members). Regardless of who are what the beneficiaries are, fewer and/or lower distributions will naturally help the assets last longer. There are many factors affecting decisions regarding the number of beneficiaries and magnitude of distributions. Some of these include:

- The degree of flexibility future beneficiaries are allowed in influencing investment or distribution-related decisions

- Preference to fund specific items (e.g., education)

- Conditions regarding family size, ability to work, drug or criminal activity, etc.

- Influencing ambitions/encouraging achievement (e.g., Warren Buffett indicated his heirs will inherit enough so they do not have to work but will most likely want to)

Without doubt, there are many factors that can influence the manner in which wealth is distributed. It is naturally a challenging task to determine guidelines for the management of substantial wealth for generations to come. Indeed, family dynamics are subject to change as is the legal landscape. There is also the delicate issue regarding how much control future generations can have over the wealth (e.g., distributions or investment strategy). Granting some control or flexibility may allow heirs to adapt to various changes. However, it may also open the door to altering the original mandate or possibly allowing some beneficiaries to raid the cookie jar. Even without this flexibility, laws and contracts are open to interpretation. So trustees can be sued for mismanagement or fiduciary breaches.

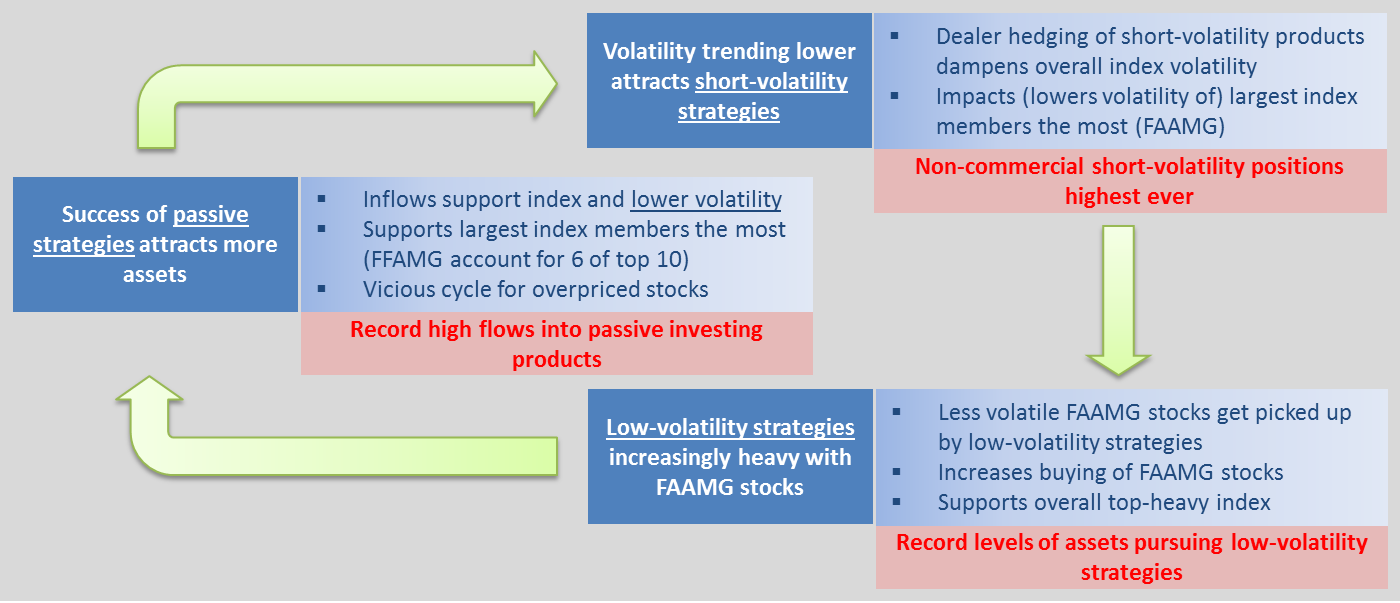

Investment Performance

While investment performance cannot be guaranteed, decisions regarding investment strategy naturally impact investment performance – and by extension, the potential magnitude and longevity of distributions. In my view, it is sensible to consider significantly higher and potentially more aggressive equity allocations than with traditional wealth management strategies.

While equities are typically assumed to have higher expected returns, most wealth strategies use bonds to diversify and reduce the overall volatility of the portfolio. The goal is to mitigate the likelihood of investors becoming uncomfortable and making bad decisions with their portfolios at inopportune times (e.g., selling during or after a market selloff).

Multi-generational wealth is different. For example, it is often administered by independent trustees instead of the beneficiaries themselves. These trustees are professionals who should know better than to fall prey to such pitfalls. Accordingly, the reason for maintaining allocations to lower growth assets such as bonds (volatility mitigation) becomes less relevant. Moreover, even if one assumes market volatility is relevant, the risk profiles of the beneficiaries (many of which may not be born) and their tolerance for market volatility are arguably more relevant than the grantor’s risk profile. Accordingly, some of the parameters that would be used to determine investment strategy are unknown.

Longevity

The third moving part is longevity; how long will the wealth last before it is entirely consumed? Longevity is perhaps the least tangible of the three factors since it will benefit many people who are not yet born or currently in the family (e.g., future spouses). Planning for an unknown set of beneficiaries naturally makes the process more challenging. For example, should one structure their wealth to benefit their currently living descendants and families? How about the next two, three, or more generations?

One concrete goal is to attempt to make one’s wealth last forever so that distributions could go on in perpetuity. However, there are laws relating to such efforts; some specifically limit the duration of trusts. Even brushing potential legal and tax issues aside, the exponential growth of families and related issues can make multigenerational strategies cumbersome to execute. The next section provides an intuitive framework for evaluating investment returns in the context of a growing family (i.e., more mouths to feed).

A Multigenerational Model

My goal in identifying the above three moving parts is to prepare the groundwork for an intuitive multigenerational model for illustrating how investment returns relate to distributions and longevity. I believe anyone making decisions in the context of a multigenerational investment strategy should consider this perspective.

My model shows how wealth grows as a multiple of initial wealth when accounting for systematic withdrawals and inflation. I believe this approach provides a valuable perspective given the exponential growth of families and the gravitational impact of inflation. Indeed, significant real returns are required to grow wealth such that it can accommodate familial growth and combat inflation in perpetuity.

I first look at real wealth multiples over a 25-year period. I believe this time frame is conservative as the average age for women to give birth in the United States is slightly higher than 25 (i.e., the true growth rate for families is slower on average). The next three figures consider scenarios based on varying levels of initial distributions (that are then grown with inflation): 2%, 4%, and 6%. This is all a gross simplification; the growth of and distributions for each family will be different. Notwithstanding, this perspective can help illustrate the relevance and provide a context for the level of investment returns for multigenerational planning.

Figure 5: Real Growth Net of Initial 2% Distribution

Initial Wealth Multiple (period: 25 years)

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

Figure 6: Real Growth Net of Initial 4% Distribution

Initial Wealth Multiple (period: 25 years)

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

Figure 7: Real Growth Net of Initial 6% Distribution

Initial Wealth Multiple (period: 25 years)

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

As we should expect, higher (nominal) returns, lower inflation, and smaller distributions result in higher real wealth multiples for each level of investment return. Figure 5 indicates a real wealth multiple of 2.4 for 3% inflation and 8% returns. In other words, using an initial 2% distribution and 3% inflation thereafter, one requires returns of approximately 8% or higher to accommodate a doubling (well 2.4x) of the family every 25 years without sacrificing the real value of the distributions. For distributions starting at 4%, returns must reach 10%. While Figure 7 does not show it, that figure goes to 11% when the initial distribution starts at 6%.

The long-term historical performance of the stocks and bonds are around 10% and 6%, respectively. This clearly highlights the need for significant equity allocations when attempting to accommodate familial growth and combat inflation. Indeed, the above results indicate that a family that doubles every 25 years needs overall returns in the 7-11% range depending upon inflation and distributions.

| Note: This discussion relates to long-term strategy and does not reflect my current tactical view on markets. As discussed in my article More Market Correction to Come, I currently view the US equity market as extremely overvalued and expect a significant correction. |

Another way to look at this is to first estimate future rate of inflation and familial growth. Given these variables, we can then determine the required investment return to support a particular level of distributions (still assuming they grow with inflation).

Figure 8: Required Investment Return

| Family doubles every 25 years / and 2% Inflation |

Family doubles every 25 years / and 3% Inflation |

Family doubles every 25 years / and 4% Inflation |

|

|

|

|

Source: Aaron Brask Capital

| Note: As a sanity check, I compared my model’s results to the 4% rule of thumb for withdrawing money in retirement popularized by William P. Bengen. I used the same 20-year period and a 50/50 portfolio Bengen used in his study. I also converted the wealth multiple back to a nominal (i.e., not inflation adjusted) figure since he did not adjust his terminal portfolio values for inflation.

While I do not have access to Bengen’s data, my results appear in line with those presented in his charts regarding terminal wealth levels. For example, his Figure 4(b) shows the wealth multiples for the above scenario in the range of 0.5-2.5x initial wealth. Integrating volatility into my model results into a two standard deviation range of 0.4-4.6x for wealth multiples. Given the number of moving parts my simplistic model did not account for (e.g., correlations), I find these results comforting – especially where the more critical downside risks are concerned.

As discussed in the following section, future scenarios will not conform to our estimates and mathematical models. However, I still believe this type of analysis is useful to relate the notions of distributions and wealth longevity to investment returns. |

Other Risks and Considerations

| “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” – George E. P. Box |

Without doubt, models are not perfect. In real-world applications, they can only attempt to simplify or reduce the dimensionality of potentially complex decisions. Below I list some risks and considerations relevant to this investment-related modeling and decisions in a multigenerational context.

- I used a simplified mathematical model in many of the example scenarios above. My goal was to highlight the logic and intuition linking multigenerational planning to investment strategy.

- In the course of planning for a particular investor, family, or entity the modeling will become more precise and involve a combination of historical and Monte Carlo simulations. This approach will better address issues around sequence of returns, volatility of parameters (e.g., inflation), correlation, etc.

- Families will grow at different rates and this growth rates change through time. This presents another factor to account for in any analysis. When real growth differs from projected growth, surpluses or deficits will occur. Planning should identify the appropriate release valve to absorb these aberrations (e.g., raise or reduce distributions).

- Even the best planning is subject to yet unknown risks. How much do we really know about how one’s family or the investment landscape will evolve over the coming decades?

- Life expectancies are rising. This may result in more generations coexisting. In other words, there may be more mouths to feed at any point in time regardless of marriage and reproductive rates. This can pose another exponential gravity on the liability side of multigenerational planning (though history indicates this growth is slow despite being exponential).

Summary and Conclusions

This article addresses the relevance or importance of pursuing higher returns for investors. In the first section, I discussed two primary types of risks investors are faced with: strategic and investment. Strategic risk relates to overall planning and setting realistic goals whereas investment risk relates to the performance of investment managers or products relative to their benchmarks. In addition to creating a plan that makes one’s goals feasible, strategic risk also relates to the ability of an investor to execute their plan. For example, some portfolios experience more volatility or tracking error than the investor is comfortable with. As such, it is important to ensure investors are likely to be comfortable with their financial plan.

The next section discussed three basic strategies to target higher returns. The first and most popular way is to increase exposures to stocks since they typically outperform bonds over the long term. This is an asset allocation decision and often revolves around one’s tolerance for market volatility. The second method was to integrate factor tilts within each allocation. For example, one could employ products, managers, or strategies that select securities based on factors have historically increased returns and are likely to do so going forward. I find the evidence for some factors (e.g., value and quality) strong enough to recommend them in virtually all cases when one is investing in stocks – assuming one can find sensibly-defined factors at a reasonable price.

The last method I highlight for increasing returns was to mitigate or remove market risk from the income stream required for retirement. This is an extremely powerful strategy as I discuss in my article on Structured Financial Planning. This approach concentrates risk in the area where it will best be rewarded (i.e., the equity market) but poses the least threat to one’s retirement.

The third and last background section discusses the concept of need versus preference when it comes to returns. Advisors should make it clear to their clients which investments and strategies are needed and which are not. Once one’s essential retirement needs are reasonably covered, investment strategy can then balance protecting and growing the excess wealth for legacy purposes (e.g., heirs and charities).

Based on the above perspectives, I get to the meat of this article and discuss the needs and preferences for higher returns in the context of the four investor types. I summarize those conclusions here:

Savers: All else equal, a typically longer time horizon and the option to work longer (or harder?) allow savers to take more risk. This can translate into significantly higher equity allocations.

Retire with just enough: Retirees who are cutting it close cannot afford to take much risk. This naturally constrains their investment options. There should be little if any equity allocations.

Significant legacy likely: By construction, one who is likely to have significant excess wealth will also have a significant buffer for taking risk before they jeopardize their own retirement. This naturally opens the door to more investments and strategies. Significant allocations to equities are typically very sensible but limited by the risk-taking capacity or volatility tolerance of the investor(s). This is why I believe my structured approach to income can be very helpful for investors of this type.

Multigenerational: Despite the obvious flexibility substantial wealth affords, preference for wealth longevity can translate into a need for significant equity allocations to accommodate the growth of a family and combat inflation. I presented a simple but useful framework for investment decisions in a multigenerational context. I also made the case for risk or volatility concerns taking a backseat since the risk will typically be managed by professional trustees who will not fall prey to emotional or rear-view decisions (e.g., sell during or after a market downturn). Moreover, the volatility will be experienced by many others who we may not yet know their risk profiles.

I have ignored many details associated with multigenerational planning as they are beyond scope of this article (and my expertise). There are, of course, tax and legal issues that should be addressed by professionals with the relevant qualifications.

About Aaron Brask Capital

Many financial companies make the claim, but our firm is truly different – both in structure and spirit. We are structured as an independent, fee-only registered investment advisor. That means we do not promote any particular products and cannot receive commissions from third parties. In addition to holding us to a fiduciary standard, this structure further removes monetary conflicts of interests and aligns our interests with those of our clients.

In terms of spirit, Aaron Brask Capital embodies the ethics, discipline, and expertise of its founder, Aaron Brask. In particular, his analytical background and experience working with some of the most affluent families around the globe have been critical in helping him formulate investment strategies that deliver performance and comfort to his clients. We continually strive to demonstrate our loyalty and value to our clients so they know their financial affairs are being handled with the care and expertise they deserve. |

Disclaimer

- This document is provided for informational purposes only.

- We are not endorsing or recommending the purchase or sales of any security.

- We have done our best to present statements of fact and obtain data from reliable sources, but we cannot guarantee the accuracy of any such information.

- Our views and the data they are based on are subject to change at anytime.

- Investing involves risks and can result in permanent loss of capital.

- Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results.

- We strongly suggest consulting an investment advisor before purchasing any security or investment.

- Investments can trigger taxes. Investors should weight tax considerations and seek the advice of a tax professional.

- Our research and analysis may only be quoted or redistributed under specific conditions:

- Aaron Brask Capital has been consulted and granted express permission to do so (written or email).

- Credit is given to Aaron Brask Capital as the source.

- Content must be taken in its intended context and may not be modified to an extent that could possibly cause ambiguity of any of our analysis or conclusions.

|